How to Resolve Upper Crossed Syndrome with Clinical Somatics Exercises

In this article I’ll explain what upper crossed syndrome is and the muscular patterns involved. At the end of the article, I describe which Clinical Somatics exercises are most effective at fixing the postural misalignment.

What is upper crossed syndrome?

The term “upper crossed syndrome” was coined by Dr. Vladimir Janda, a Czech neurologist, professor, and researcher. Dr. Janda was a pioneer in the field of rehabilitation, and he founded the rehabilitation department at Charles University Hospital in Prague, Czechoslovakia. His work was in line with what we teach in Clinical Somatics: that the function of the nervous system can lead to muscular imbalances and dysfunctional posture and movement, which in turn can lead to chronic pain syndromes.

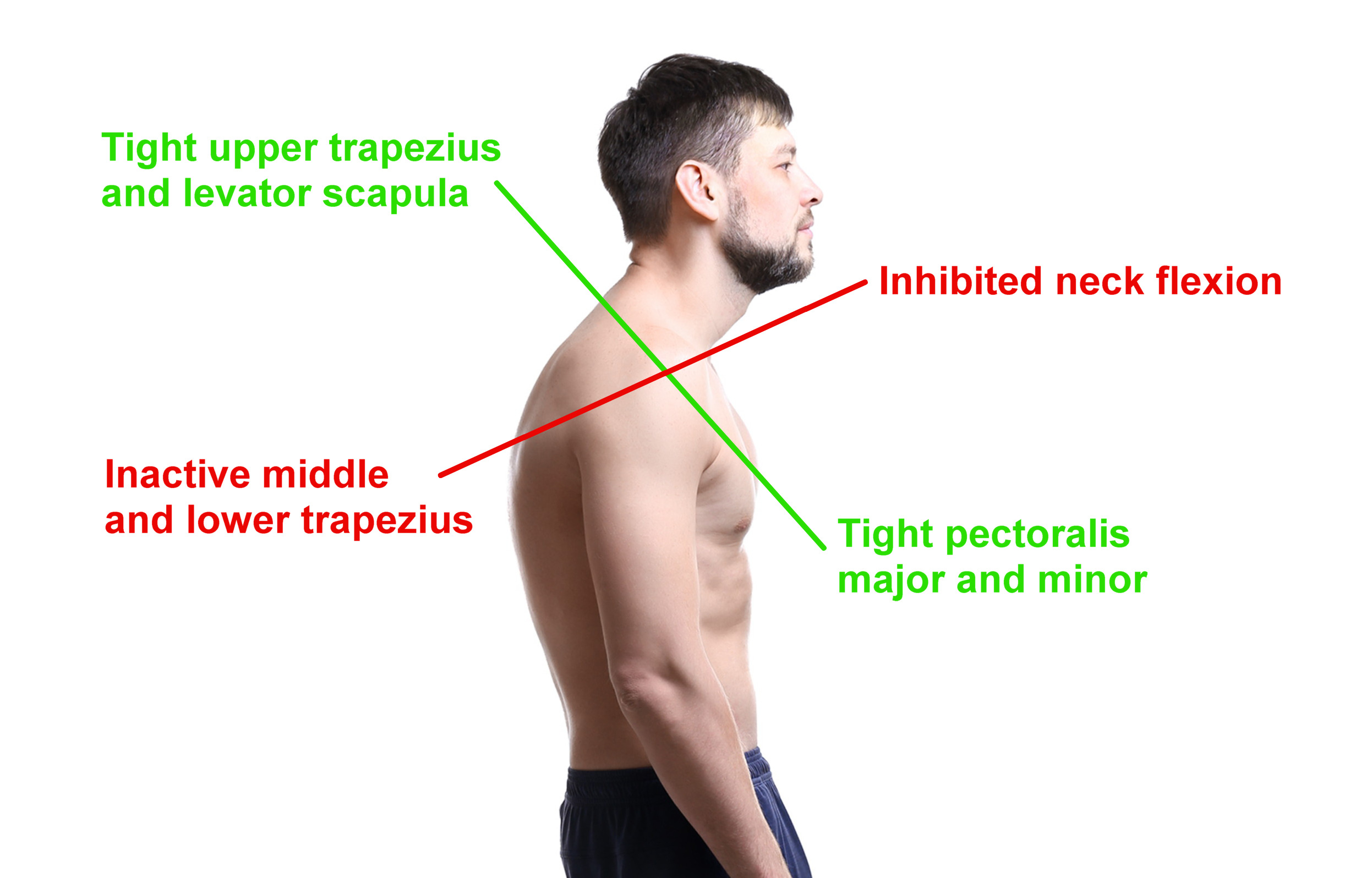

Upper crossed syndrome describes a pattern of tight and “weak” or inactive muscles in the upper body. As shown in the diagram at the top of this post, these tight and weak muscles form an X when viewed from the side of the body.

In this pattern, the pectoralis major and minor muscles are tight, rounding the shoulders and upper back and making the chest concave. Chronic tension in the pectorals inhibits the action of the middle and lower trapezius, rendering them inactive and making them appear to be weak.

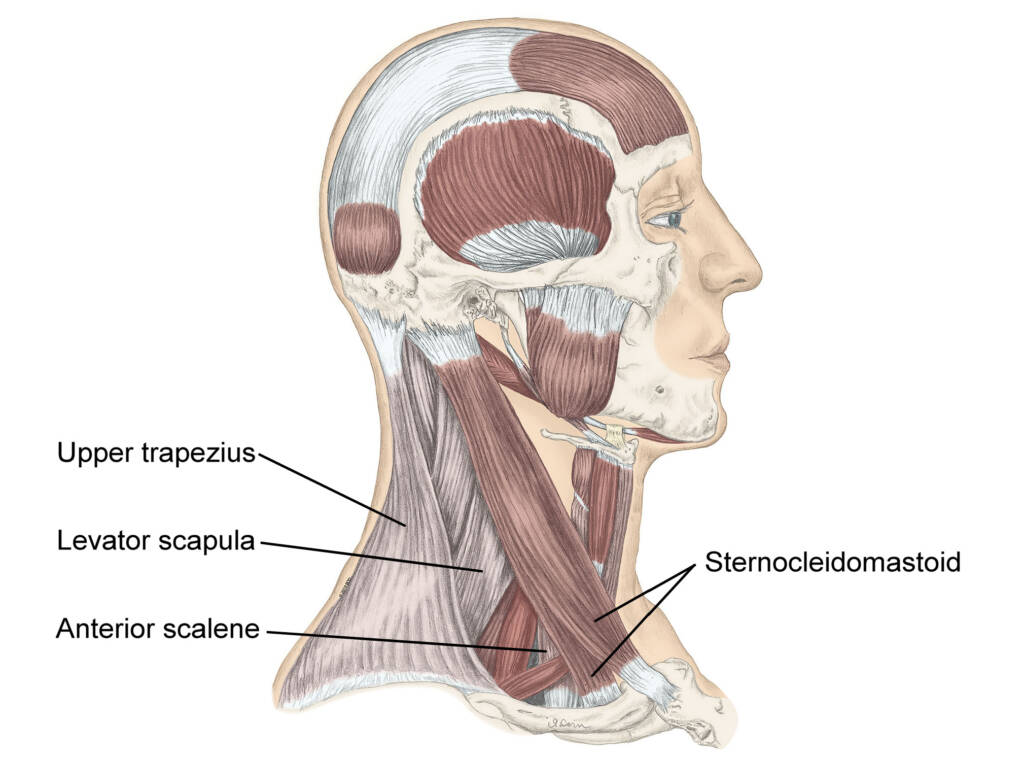

As the pectorals become tighter, they pull the shoulders, neck, and head forward. In order to stay balanced, a person with very tight pecs and rounded posture will then tip their head upward so they can look straight ahead. This engages the upper trapezius and levator scapula, which become chronically tight, compressing the cervical spine. Forward flexion of the neck (tucking the chin and bringing the head down the chest) becomes inhibited; the muscles that do this action are the sterncleidomastoid, anterior scalene, longus capitis, and longus colli. However, the sternocleidomastoid and anterior scalene are still active, holding the head forward of the spine in forward head posture.

In Clinical Somatics, we refer to this postural pattern as Red Light Posture or the Withdrawal Response. It is also called postural kyphosis, and is thought of as “computer posture.” Upper crossed syndrome involves forward head posture, though forward head posture can in theory exist without the concave chest and rounded upper back.

If you have upper crossed syndrome, you may be told to strengthen your upper back muscles so you can stand up straight. But working to strengthen or activate the inactive upper back muscles will not be productive unless you also release the chronically tight pectorals, which are at the root of this pattern. As the pectorals release, you’ll be able to stand up straight easily and without effort.

Upper crossed syndrome may occur along with or be a causative factor in the following conditions:

- Forward head posture

- Neck tension and pain

- Degeneration of the cervical spine

- Compression of the cervical nerves

- Shoulder tension and pain

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

- Shallow breathing

- Back tension and pain

- Lower crossed syndrome

Why do we develop upper crossed syndrome?

Why do our pectoral muscles become tight enough to cause upper crossed syndrome? And why does it happen to some people and not others?

The movement and level of contraction of our muscles is controlled by our nervous system. The way that our muscles move, and how much we keep them contracted, is actually learned over time by our nervous system.

Our nervous system learns certain ways of using our muscles based on how we choose to sit, stand, and move each and every day. Our nervous system notices the postures and movements that we tend to repeat, and it gradually makes these postures and movements automatic so that we don’t have to consciously think about them.

This learning process—that of developing what we refer to as muscle memory—allows us to go through the activities in our daily lives easily and efficiently. Unfortunately, if we tend to repeat unnatural postures or movements, our nervous system will learn those too. Our automatic neuromuscular learning process doesn’t discern what is good or bad for us—it just notices what we tend to repeat, and makes it automatic.

Upper crossed syndrome can result from a number of different activities and habits. The most common cause of upper crossed syndrome is use of computers and smartphones, which involves spending a lot of time looking downward, often with our head craned forward and our arms and shoulders rotated inward. This causes us to develop chronic tension in the pectorals, which can easily lead to upper crossed syndrome posture.

In a similar way, any repetitive activity or profession that involves looking downward and working on a surface below eye level—like being a chef or working on an assembly line—can lead to upper crossed syndrome.

Stress is another major factor in this posture. When we feel stressed, tired, or worried, we instinctively round our back and contract the muscles on the front of our torso. In the past, this withdrawal reflex was a way to protect the most vulnerable parts of our bodies. Now, this reflex simply leads to poor posture, tight muscles, and chronic pain.

Certain types of athletes tend to develop upper crossed syndrome, the most common ones being gymnasts and weightlifters. Both gymnastics and weightlifting demand a great deal of strength in the chest, and when the tension in the pectorals becomes out of balance with the upper back muscles, even highly trained athletes can develop upper crossed syndrome.

As your nervous system gradually learns to keep your muscles tight, gamma loop activity adapts. This feedback loop in your nervous system regulates the level of tension in your muscles. As your brain keeps sending the message to contract your muscles, gamma loop activity adapts and starts keeping your muscles tight all the time.

Meanwhile, your proprioception (your internal sense of your body position) adapts so that you’re not aware of the increased level of tension in your muscles. Your proprioception also adapts to your body position; so as your nervous system gradually starts holding your lower back in an arch and your pelvis tilted forward, it will feel to you as though your lower back and pelvis aligned correctly.

The most effective Clinical Somatics exercises to resolve upper crossed syndrome

First, if you’re not familiar with pandiculation and why it’s the most effective way to reset gamma loop activity and release chronic muscle tension, I recommend that you read What is Pandiculation?

Below I’ve listed the exercises from the Level One & Two Courses that are most helpful for releasing the pattern of muscle contraction present in upper crossed syndrome. Pandiculation exercises don’t just release chronic muscle contraction—they also improve voluntary control of inactive muscles. So, there are exercises listed below that work with the pectorals, upper trapezius, and levator scapula as well as with the middle and lower trapezius and neck flexors.

If you’re just starting your Clinical Somatics practice, be sure to read Developing Your Own Daily Practice.

LEVEL ONE COURSE

Arch & Flatten: This exercise is the most basic movement in Clinical Somatics. It allows you to release and regain voluntary control of the extensors of the lower back and the abdominals, and maintain neutral pelvic alignment. While this movement does not work directly with the muscles involved in upper crossed syndrome, it’s common for upper crossed syndrome to occur along with either anterior or posterior pelvic tilt. It’s important to address patterns of tension in the core of the body first, as our core is where our posture and movement patterns begin. Tension and misalignment in the upper spine can be simply a reaction to an imbalance in the lumbar spine and pelvis, so the Arch & Flatten is an essential exercise to practice daily.

Arch & Curl: This exercise pandiculates the abdominals, pectorals, and neck flexors, directly addressing upper crossed syndrome. This is also an essential exercise to practice daily.

One-sided Arch & Curl and Diagonal Arch & Curl: These have the same benefits as the Arch & Curl, but they focus on one side of your body at a time, allowing you to even out imbalances in your muscular patterns.

Back Lift: This exercise allows you to release and regain control of the upper, middle, and lower trapezius, along with the lower back and gluteal muscles. If you have significant rounded posture, you may find this exercise uncomfortable at first. You may need to make progress in releasing your pectorals before practicing this exercise comfortably.

Upper Trapezius Release: This movement (found at the end of the Bonus: Ultimate Pandiculation video) releases the upper trapezius and levator scapula.

Flowering Arch & Curl: This is a full-body version of the Arch & Curl, involving arching and curling of the back, internal and external rotation of the arms, and internal and external rotation of the hips. You can practice just the upper body portion of this movement to focus on the muscles involved in upper crossed syndrome, or include the leg movement if you wish.

LEVEL TWO COURSE

Head Lifts: This exercise pandiculates the muscles involved in forward head posture: the sternocleidomastiod and anterior scalenes.

Proprioceptive Exercise 1: This is a very important exercise for anyone with upper cross syndrome to practice regularly, as it allows you to retrain your posture and proprioception (your internal sense of your body position). This exercise is practiced seated in a chair in front of a full-length mirror, allowing you to compare how your posture feels internally to what you see in the mirror.

Scapula Scoops Part 1: This exercise pandiculates the upper and lower trapezius and levator scapula.

Scapula Scoops Part 2: This exercise pandiculates the pectorals and the middle trapezius.

Diagonal Curl: This exercise releases the pectorals and abdominals; it is an excellent exercise for opening up the chest.

Breathing Exercises: If you find that your breathing is shallow due to chronic tension in your chest and abdominals, these breathing exercises will help you regain voluntary use of your diaphragm and take fuller, deeper breaths.

Recommended reading:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna