You can listen to Sarah’s podcast on this topic here:

How the Withdrawal Response Leads to Rounded Posture

What is the Withdrawal Response?

You’re walking down the street and hear gunshots behind you. Within just fourteen milliseconds, your jaw muscles begin to contract. At twenty-five milliseconds, your upper trapezius muscles contract, raising your shoulders and bringing your head forward. At thirty-four milliseconds, the muscles of your eyes and brow contract, squeezing your eyes shut.

These lightning-fast neural impulses continue down your body, making your elbows bend, arms rotate inward, abdominal muscles contract, inner thigh muscles and hamstrings tighten, and knees and ankles roll inward. The withdrawal response pulls your extremities inward and brings you into a crouched position, protecting the most vulnerable parts of your body from attack.

The Negative Effects of the Withdrawal Response

The withdrawal response has helped us survive and get to where we are today. But for those of us now living in industrialized societies in which our lives are not being threatened on a regular basis, the withdrawal response is not doing us any favors. The never-ending demands of work, family life, financial responsibilities, and social expectations are constantly present in our minds, and we perceive these stressors to be life-threatening.

When we experience these types of chronic psychological stress our withdrawal response is constantly activated, contracting our abdominal muscles and bringing us into the rounded posture we associate with aging. When this posture becomes habitual, we experience back and neck pain as well as a host of other physiological dysfunctions including shallow breathing, high blood pressure, and digestive issues. As Moshe Feldenkrais said, “Should the environment change too sharply, the reflex reaction may be the doom of the species as surely as it has served it.”

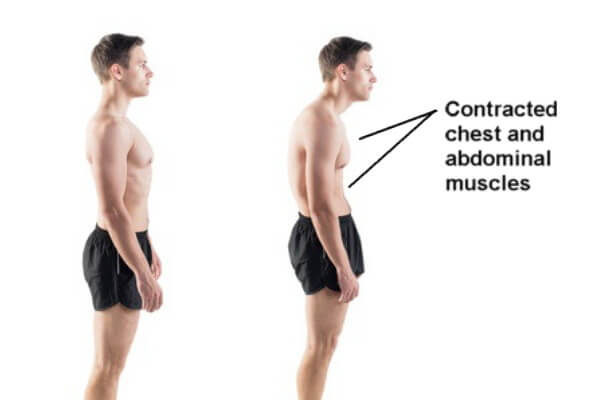

The abdominal muscles are central to the withdrawal response. When they are chronically contracted, the head and ribcage are pulled forward and held there as if we’re doing a stomach crunch. Chronic contraction of the abdominals results in hyperkyphosis, the rounded posture we associate with aging. Hyperkyphosis occurs when the natural kyphotic curve in the thoracic portion of our spine becomes exaggerated. This rounded posture is often blamed on osteoporosis or old age, which doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. Bones don’t move out of alignment unless muscles tell them to, and the fact that bones have become weak and brittle does not directly affect whether we adopt a rounded, straight or arched posture.

People with hyperkyphosis and “forward head posture” are shown to have significantly more neck pain and disability than people with normal posture, and the further forward they hold their head, the greater their pain.

For every inch the head moves forward, it effectively gains ten pounds in weight because of the increased strain on the muscles of the neck and upper back. The suboccipital muscles, just below the base of the skull, must contract even further to lift the head up to face forward instead of looking down at the ground. Pain can result simply from all of these muscles being chronically contracted, and in addition, disc problems and nerve pain may develop from the increased compression of the cervical spine.

Hyperkyphosis can also cause back pain. When the abdominals contract and the weight of the head and ribcage are pulled in front of our center of gravity, we quite literally will fall forward if we don’t do something to balance ourselves out. So as the abdominals gradually become habitually contracted, the back muscles must work harder and harder to keep us upright in gravity. A person with hyperkyphosis may complain only of a sore back, but all attempts to treat the back muscles directly will have little effect until the underlying cause—the habitual abdominal contraction—is addressed.

In addition to causing pain and cervical disc degeneration, chronically contracted abdominals have negative effects on many other functions of the body. Tight abdominals limit the ability to take a full breath, which demands that the diaphragm be able to contract downward and push the contents of the abdomen forward. If the abdominals are tight, this action cannot occur and breathing becomes shallow and strained. Chronic tightness and compression in the front of the body also puts pressure on all the internal organs, contributing to high blood pressure, digestive problems, frequent urination, constipation and impotence.

The abdominal muscles are the strongest and most central muscles acting in the withdrawal response. However, habitual contraction of the internal rotators and flexor muscles of the extremities can cause health problems as well. The withdrawal response contracts the inner thigh muscles, rotating the thighs inward; this places stress on the knees and ankles and makes the arches of the feet collapse. Hip flexors, quadriceps and hamstring muscles become tight and sore from holding the body in a flexed position. Headaches, teeth grinding, TMJ disorders, and bruxism (ringing in the ears) can develop due to constant contraction of the neck and jaw muscles.

How and Why We Habituate the Withdrawal Response

The effects of the withdrawal response tend to be more obvious in the elderly, simply because they have been alive longer and have had more exposure to stress. But there are two important things to note here.

One, it is not inevitable that we will develop rounded posture as we age. The way that we perceive and cope with stress throughout our lives determines how the systems of our body react. Learning how to deal with stress in a constructive way can prevent you from automatically triggering your withdrawal response and suffering the negative physical effects.

Two, we can develop rounded posture at any age. There is a fairly recent shift in our daily lives that has caused many people to begin developing hyperkyphosis during their twenties and thirties, teens and even earlier. I am talking about the advent of personal computers, smart phones, and the myriad of other devices which keep us constantly connected and entertained.

Spending hours upon hours sitting at a computer keeps us in the withdrawal response posture: hips and knees flexed, arms rotated inward, and head and shoulders rounded forward. It takes a great deal of conscious attention, as well as proper seating, to prevent this posture from becoming habitual.

There are still other factors which contribute to rounded posture:

- Fatigue, which in and of itself is often stressful, makes us want to curl up in a ball and go to sleep. Chronic lack of sleep alone can cause someone to slouch and adopt the withdrawal response posture.

- People who are quite tall often develop rounded posture as a result of functional needs like working at a counter top built for average height people, or as a result of feeling insecure and wanting to fit in by shortening their stature.

- Abdominal surgery or injury often results in withdrawal response posture, as people instinctively want to protect the painful area by contracting the muscles around it.

- Athletic training that demands a great deal of core strength, such as swimming or gymnastics, can cause even the most highly trained athletes to have rounded shoulders and sunken chests.

- Simply being cold on a regular basis can contribute to withdrawal response posture. Notice what happens next time you feel really cold: you’ll bring your arms in toward your body, round your shoulders and raise them up, and if you’re sitting or lying down you’ll contract your abdominals and curl up into the fetal position to stay warm.

Reversing the Effects of the Withdrawal Response

All of these negative effects of the withdrawal response can be prevented, alleviated, and often eliminated by re-educating the nervous system to release the chronic muscular contraction in the abdominals, chest muscles, and internal rotators and flexor muscles of the extremities. In order to re-educate the nervous system, we must go through an active learning process involving slow, conscious movement.

The most effective way to teach the nervous system to release chronic muscular tension is with the movement technique of pandiculation. Pandiculation sends accurate biofeedback to the nervous system, resetting the gamma feedback loop, which controls the resting level of tension in our muscles. Thomas Hanna developed the technique of pandiculation and incorporated into his system of neuromuscular education called Clinical Somatic Education.

Check out the other two posts in this series about reflexes and posture:

Recommended reading:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna