Understanding the Pelvic Floor Muscles and Pelvic Pain

What is the pelvic floor?

The pelvic floor is a large sheet of skeletal muscle that forms the base of the abdomen. It is made up of the levator ani (subdivided into the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles) and the coccygeus muscles, and associated connective tissue. Both men and women have a pelvic floor.

The pelvic floor, also referred to as the pelvic diaphragm, has the important job of providing support for the pelvic and abdominal organs. It helps to maintain continence, facilitate childbirth, and regulate intra-abdominal pressure, which affects organ function.

Common problems resulting from or related to chronic tightness, weakness, or injury to pelvic floor muscles and nerves include:

- Urinary incontinence

- Inability to have bowel movements

- Pelvic organ prolapse

- Intra-abdominal hypertension

- Abdominal compartment syndrome

- Pain or spasm in the pelvic floor muscles

- Tailbone pain

- Sexual dysfunction

- Nerve compression resulting in pain, tingling, numbness, and muscle weakness or lack of control

Common causes of problems with the pelvic floor muscles include:

- Injuries to the pelvic area

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Pelvic surgery

- Being overweight

- Advancing age

- Overusing the pelvic muscles by going to the bathroom too often or pushing too hard

- Sexual trauma

- Chronic and acute stress

How compression of pelvic nerves causes pain

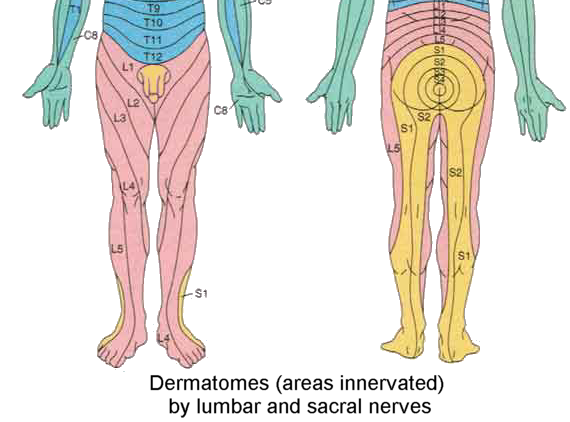

Before we discuss the tight muscles that can cause pelvic pain and how to release them, it’s important to learn about some of the nerves involved. The pelvis is a high-traffic area when it comes to nerves. Nerves that emerge from the lumbar and sacral spine innervate (supply with sensation and motor control) the pelvic region and control its many functions, and travel downward to innervate the lower half of the body.

A compressed, entrapped, or “pinched” nerve occurs when misaligned bones, cartilage, connective tissues, or tight muscles put pressure on a nerve. This pressure can cause pain, tingling, numbness, and muscle weakness or lack of muscular control.

The coccygeal plexus of nerve fibers is formed by the 4th and 5th sacral nerves and the coccygeal nerves. It innervates the pelvic floor muscles (coccygeus and levator ani), the sacrococcygeal joint (where the sacrum and tailbone meet), and the skin between the coccyx and anus. Misalignment of the sacrum, coccyx, and tight pelvic floor muscles could compress the coccygeal plexus of nerves.

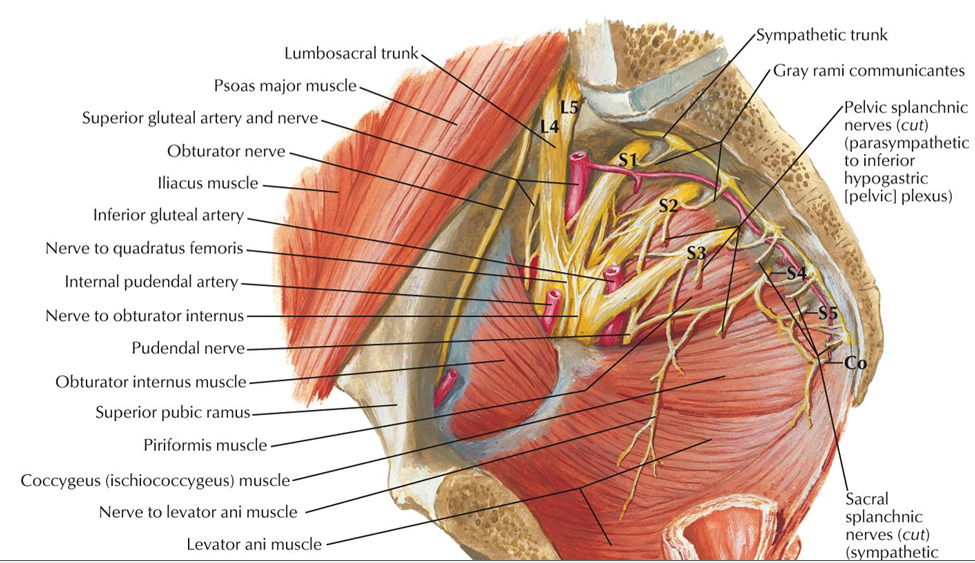

The pudendal nerve is formed from the 2nd through 4th sacral nerves (see diagrams below). It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, passes between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles, passes between the sacrospinous ligament and sacrotuberous ligament as it enters the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen, and then travels through the pudendal canal (aka “Alcock canal”) on its way to its final destinations. Compression of the pudendal nerve can occur at any point along its path.

The diagrams below show the pudendal nerve and its branches, which innervate the muscles and skin of the perineum, pelvic floor, and sexual organs. If this nerve is compressed, it can cause sexual dysfunction, incontinence, pain, and loss of sensation and muscular control. Misalignment of the sacrum and pelvis, chronic tightness in the piriformis or coccygeus muscles, and pressure on the pudendal canal and the terminal nerve branches can all cause compression of the pudendal nerve. Pudendal nerve entrapment, also known as Alcock canal syndrome, is common among male cyclists due to the excessive and repetitive pressure put on the pudendal canal.

Pelvic autonomic nerves originate from the abdominal aortic plexus and lumbar and sacral sympathetic nerves. They innervate the pelvic cavity and control automatic functions including blood flow, hormone secretion, urination, defecation, erection, and orgasm. Since these nerves originate from a large area—the abdomen all the way down through the 3rd sacral vertebrae—compression can occur at a number of places. To alleviate compression of pelvic autonomic nerves, muscle tension and misalignment throughout the abdomen, lower back, and pelvis must be addressed.

How chronically tight muscles cause pelvic pain

In Clinical Somatics, we work with releasing patterns of muscle tension involving multiple muscles and an overall posture or movement pattern, instead of focusing on individual muscles—which rarely solves the problem. Muscles don’t work alone; they work in teams with other muscles to help us stand and move in various ways. So if one muscle is tight, other muscles that perform the same or a similar action are likely tight as well. We must release the entire pattern of muscle tension in order to truly solve the issue.

There are three basic patterns of muscle tension that we humans tend to develop in the core of our body, and all three of these patterns can contribute to pelvic pain in some way.

The first pattern is the action response posture, which is the posture we naturally assume when we’re ready to move or take action, or when we want to appear confident. We arch our lower back, externally rotate our hips, and stick out our chest. Repeatedly coming into this posture makes the lower back muscles and external hip rotators (the gluteal muscles) chronically tight. When these muscles are tight, the lumbar and sacral vertebrae are compressed and the sacrum can be pulled out of alignment. This causes compression of the nerves that exit the spine in between the lumbar and sacral vertebrae. And since the piriformis muscle is an external hip rotator, this pattern of tension can compress the pudendal nerve as it passes between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles. So, it is easy to see how the action response posture can lead to pelvic pain and dysfunction.

The second pattern of tension is the withdrawal response, which is the opposite posture. When we are scared, experience negative stress or trauma, tired, or simply want to withdraw from our environment, we contract our abdominals (and other core muscles including the iliopsoas and pelvic floor muscles) and bring our limbs in closer to the center of our body. Repeatedly coming into this posture makes the abdominal muscles chronically tight and causes us to stand with rounded posture.

The withdrawal posture can compress the pelvic autonomic nerves as they originate in the abdomen, and is a likely cause of chronic tension in the pelvic floor muscles. Chronic tightness in the abdominals and pelvic floor muscles compresses the abdominal and pelvic organs, can be painful, and can cause problems with elimination and sexual function.

The third common pattern of tension we tend to develop is the flexor reflex posture, in which we bend to one side or hike one hip up higher than the other. This posture often develops as a result of an injury or repetitive activity. We may contract the muscles on one side of our body in order to protect a body part from pain, or we may simply overuse or misuse one side of our body repeatedly as we go through our daily life.

The flexor reflex posture brings the lumbar and sacral spine and the pelvis out of alignment by curving the spine, raising one hip higher than the other, and/or by rotating or torquing the pelvis. This misalignment can lead to compression of the lumbar and sacral nerves. The flexor reflex posture can also involve chronic tightness in the external hip rotators on one side, which can compress the pudendal nerve.

Most of us tend to come into all of these postural patterns to some degree in our daily lives, but often one or two of the patterns will dominate. As you explore the cause of your pelvic pain, it’s important to notice how you may be habitually coming into these postures. The cause of your pain is almost always related to how you use your entire body.

Unraveling your pelvic pain: Changing habits, addressing stress, and releasing your muscles

Changing habits

If you’re trying to relieve your pelvic pain, the first and most straightforward thing to ask yourself is: Could any of my regular activities be causing or contributing to my pain? This could include, but is not limited to:

- Cycling

- Horseback riding

- Sports that involve kicking and abrupt directional changes

- Heavy weightlifting

If you think that any of your regular activities might be contributing to your pain, commit to taking a break from the activity while you pursue a healing process.

Addressing stress

As I mentioned in the previous section, negative stress and trauma often cause us to adopt the withdrawal response posture, which involves contracting the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles. If you feel that stress or trauma might be playing a role in your pelvic pain, I encourage you to pursue talk therapy or any other type of therapy that allows you to effectively reduce your stress and address trauma. Finding a way to address your stress or trauma may be a key component in allowing you to get out of pain.

Releasing your tight muscles with pandiculation

Pandiculation is an extremely effective way to address pelvic pain, whether the pain is caused by nerve compression, tight pelvic floor muscles, or both. Put simply, pandiculation involves slowly contracting a muscle or group of muscles and then very slowly releasing against resistance or gravity. This sends accurate biofeedback to the nervous system about the level of contraction in the muscle/s, and gradually resets the baseline level of muscle tension being set by the nervous system. As muscles release, the spine will be decompressed and the sacrum and pelvis can shift back into healthy alignment.

In addition to releasing chronic muscle tension, pandiculation increases voluntary control of muscles—and voluntary control is very important when it comes to pelvic floor muscles, which need to be able to contract and release as needed.

*If your pelvic pain is caused by an injury, pandiculation exercises can help you heal by gently increasing your muscular control and range of motion and improving circulation.

If you have pelvic pain, here are the exercises from the Level One & Two Courses that are most likely to help you. However, don’t skip the other exercises in the courses; everyone’s patterns of muscle tension are slightly different, and there are benefits to be experienced from every exercise. Learn just one exercise at time, practice it gently, and notice the effects that it has on your body. Depending on your areas of tension and pain, certain exercises may not be comfortable for you—so take it slow as you learn each new exercise, and skip the ones that don’t feel good for your body.

Level One Course:

Arch & Flatten

Back Lift

Arch & Curl

Side Curl

One-sided Arch & Curl

Iliopsoas Release

Diagonal Arch & Curl

Hip Rotation

Level Two Course:

Pelvic Clock

Proprioceptive Exercise 1

Big X

Proprioceptive Exercise 2

Gluteal Release

Diagonal Curl

Hip Directions

Breathing Exercises

And be sure to practice the Kegel!

If you have any issues with your pelvic floor muscles or pelvic pain, you’ve likely heard of Kegel exercises. A Kegel exercise consists of contracting your pelvic floor muscles and then releasing them. If you’re not sure how to contract your pelvic floor muscles, I recommend reading this quick guide to Kegel exercises:

Step-by-step guide to performing Kegel exercises – Harvard Health

As described in that guide, you should gradually increase the time it takes you to contract and release your pelvic floor muscles in order to improve your muscular control.

The more slowly you release, the more effectively you’ll be pandiculating your pelvic floor muscles and releasing chronic tension. So if you know that your pelvic floor muscles are chronically tight, you should spend more time and focus on the release phase of the Kegel. But if your pelvic floor floor muscles are inactive or lax, then the even counting (same amount of time for the contraction and release phase) will likely be more helpful for you.

Recommended reading:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna