You can listen to Sarah’s podcast on this topic here:

What is the stretch reflex (myotatic reflex)?

From a young age, we’re taught that stretching is a necessary part of any workout routine. If we’re involved in sports or physical training, we stretch to warm up, cool down, and during breaks to help us stay loose. Unfortunately, stretching usually doesn’t accomplish much, mainly due to the myotatic reflex, more commonly referred to as the stretch reflex.

The stretch reflex is a function of the gamma loop, a feedback loop in our nervous system that regulates the level of tension in our muscles. If you’re not familiar with the gamma loop, you can read What is the Gamma Loop?

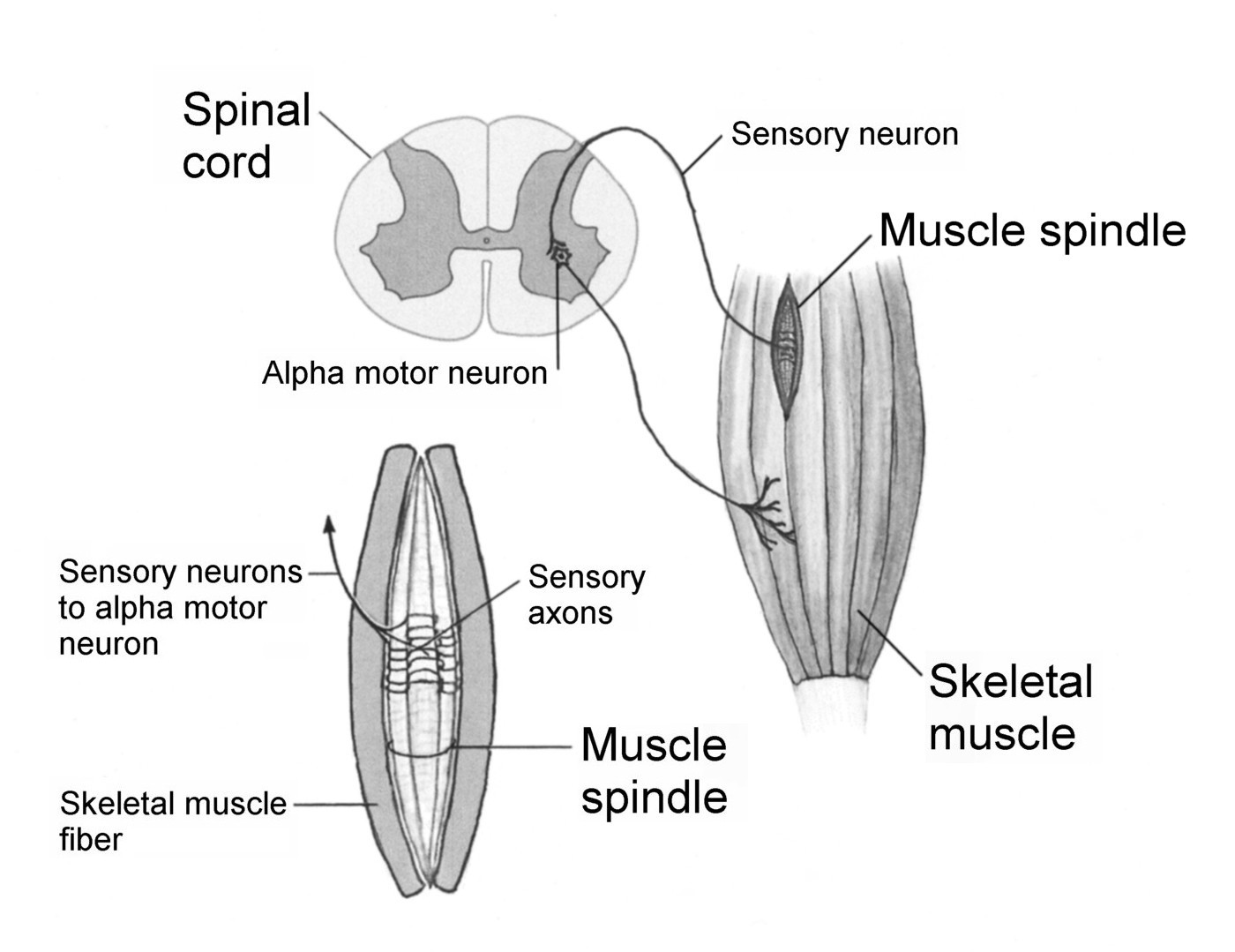

Muscle spindles play an important role in our stretch reflex. Muscle spindles are sensory receptors located within our skeletal muscles (the type of muscles that move our skeleton around, in contrast to the smooth muscle of our internal organs). Muscle spindles detect changes in the length of our muscles, and for this reason they’re also referred to as stretch receptors.

When one of your skeletal muscles is stretched—either by you pulling on it, someone else pulling on it, or by someone giving you a deep massage—the muscle spindles within that muscle are stretched too.

As you can see in the diagram below, the sensory axons wrapped around the muscle spindle sense the increase in length and send that information to the alpha motor neuron in the spine. The alpha motor neuron then tells the skeletal muscle fibers to contract. Why? To keep us standing upright and to prevent our muscles from being torn.

Why do we have the stretch reflex?

In general, reflexes exist to help us stay alive and avoid injury. In fact, the neurons carrying the stretch reflex messages back and forth from the spine are among the most heavily myelinated (insulated) in the body. This means that their messages travel faster and are more important to our survival than the sensations of pain, touch, and temperature.

One critical function of the stretch reflex is that it helps us stand upright. If you suddenly lean to the right side, the postural muscles on the left side of your vertebral column are stretched. When the muscle spindles in those muscles sense that they’re being lengthened, they automatically send the message to contract to correct your posture. We’re rarely consciously aware of how the stretch reflex automatically maintains our balance and keeps us from falling over—but we sure would notice if it wasn’t working properly.

The stretch reflex also prevents us from tearing our muscles. The knee-jerk reflex is a great example of the stretch reflex. When the doctor taps your patellar tendon just below your knee, it stretches your patellar tendon, your quadriceps tendon, and your quadriceps muscles. The muscle spindles in your quadriceps sense the sudden increase in length and automatically send the message to contract your quadriceps to prevent injury and overstretching. When your quadriceps contract, your foot kicks up. Absence of this reflex could indicate a possible a neurological disorder, like receptor damage or peripheral nerve disease.

When we practice static stretching (the type of stretching traditionally taught in athletic training), the voluntary and involuntary parts of our nervous system are battling each other, trying to achieve opposite results. Our brain is sending the voluntary message to manually stretch our muscles by pulling on them. But despite all our efforts, our stretch reflex is automatically kicking in, contracting our muscles to prevent us from overstretching and tearing our muscles.

So—static stretching doesn’t work?

That’s right—static stretching doesn’t actually change the resting level of tension in your muscles that’s being set by the gamma loop. In fact, manual lengthening in general, including massage and using a foam roller, does not have a lasting effect on how your nervous system is controlling the level of tension in your muscles.

The only way to have a lasting effect on the level of tension in your muscles is by educating your nervous system. This is how you built up the muscle tension in the first place, after all. But while your muscles became tight as a result of the automatic, often subconscious learning process of developing muscle memory, you must use a voluntary, conscious learning process to release them.

Pandiculation naturally reduces the level of tension in our muscles by providing accurate biofeedback to our nervous system about the level of tension in our muscles. This gradually restores normal, baseline activity in the gamma loop and a healthy level of muscle tension.

If stretching doesn’t work, why does it sometimes make us feel more flexible?

You can read about three reasons why stretching might make you feel more flexible, as well as my personal transition from stretching to pandiculating, in my post Why Stretching Doesn’t Work.

If you’re a yoga practitioner, I also recommend reading Combining Your Clinical Somatics and Yoga Practices.

If stretching doesn’t work, then why did humans start stretching in the first place?

The practice of static stretching, which can be traced back to ancient Greece, likely evolved as an intellectual interpretation of our natural instinct to pandiculate. People may have thought that if it feels good to actively stretch our muscles for a few moments, then even more benefit would be had by forcibly stretching them for longer periods of time.

At this time in history, understanding of the human nervous system wasn’t nearly advanced enough to understand the stretch reflex. It was believed—as it still is today, even though we now have the science that proves otherwise—that muscles and connective tissues could be lengthened by passively stretching and massaging them.

The practice of static stretching and the belief that it works persists in most sports programs, gyms, yoga and dance studios, and physical therapy and chiropractic clinics. Even though many people know from experience that static stretching doesn’t help their chronic tightness or pain, it’s difficult to argue against a practice that’s been around for more than 2000 years. Hopefully, as Clinical Somatics and the movement technique of pandiculation become more widely known, we’ll move past this archaic practice and start lengthening our muscles in a far more effective, natural way.

Recommended reading:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna