Let There Be Light! Making the Most of Your Serotonin and Melatonin

Humans evolved living outdoors, exposed to bright natural light during the day and total darkness at night. The systems of our body rely on natural light to keep us healthy—our eyes and skin actually need to be exposed to daylight in order for our brains and bodies to function optimally. We need darkness too, so that our circadian clock can regulate our sleep cycle and other bodily functions.

Yet sadly, a 2019 study showed that we spend just 2% of our time (94 minutes per week) outdoors. And it’s not just adults; children spend just 4 hours per week playing outside.

Spending our lives indoors has led to increasing rates of depression, poor cardiovascular health, nearsightedness, asthma, and insomnia. Childhood rates of mental illness, nearsightedness, asthma, and poor cardiovascular fitness have increased significantly in recent years as well, and children reportedly experience symptoms of seasonal affective disorder during summer months simply because they spend most of their day indoors.

Part of the reason for the rising rates of these conditions is that we need exposure to daylight in order to produce adequate serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in a wide range of physiological processes. And serotonin is the precursor to melatonin—it gets converted to melatonin in darkness. Melatonin is necessary for regulating our sleep-wake cycle as well as our immune system. If you’re not spending time outside every day, your health is likely suffering because of it.

In this post I’ll talk about what serotonin and melatonin do in our brains and bodies, how we produce them, what happens when their levels are low, and how to naturally boost your serotonin and melatonin.

What is serotonin, and how do we produce it?

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps to regulate mood, social behavior, learning, cognition, memory, cardiovascular function, sensorimotor function, pain sensation, appetite, bowel motility, bladder control, sleep, and sexual desire. Whew!

Serotonin is found in the central nervous system, blood platelets, and the mucosa of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Approximately 95% of our body’s serotonin is in our gut. Enterochromaffin cells in our gut lining release serotonin, which regulates peristaltic waves (movements of muscles that move food through our digestive tract) and enzyme secretion. Our gut produces the serotonin that it needs locally. So if you have any issues with gut motility, you should make healing your gut a priority; a healthy gut is necessary in order to produce healthy levels of serotonin.

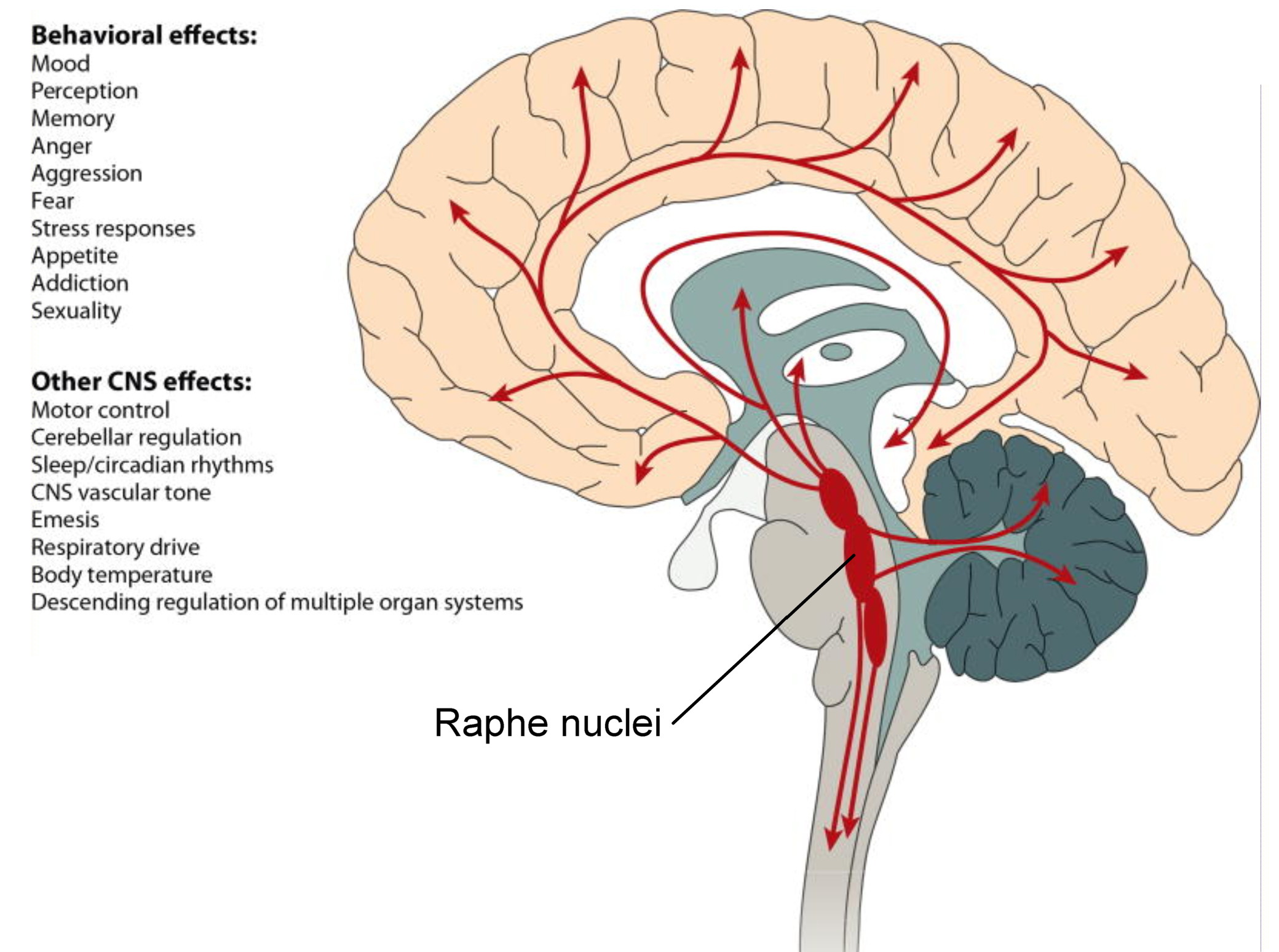

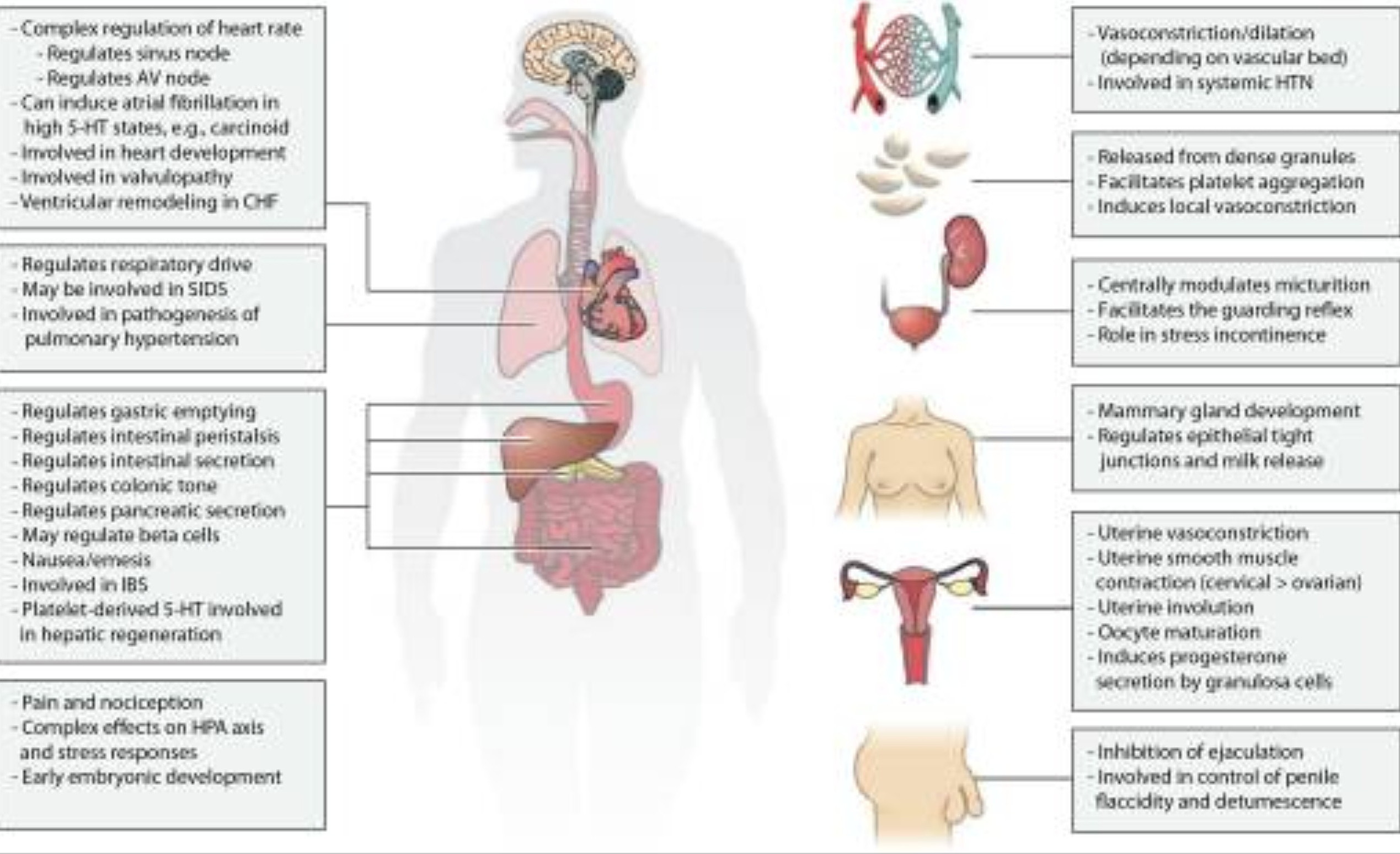

Figures 1 and 2 from The Expanded Biology of Serotonin, March 2018.

The brain also produces the serotonin that it needs locally. Serotonin is produced in the brain by the raphe nuclei in the brainstem, as shown in Figure 1 above. When bright light enters the eyes, retinal ganglion cells send signals to serotonin-producing neurons in the raphe nuclei (RN); this is referred to as the retino-raphe tract (see diagram below).

Figure 1. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood, August 2019.

The more bright sunlight we’re exposed to, the more serotonin we produce. But the retino-raphe tract isn’t the only reason. Scientists have found that our skin produces serotonin when exposed to sunlight as well. Like our gut and brain, our skin produces serotonin for local use: serotonin helps to regulate the immune and vascular systems of the skin.

Researchers in Germany found that photostimulation (stimulation by light) of serotonin by the skin also increases levels of serotonin in the blood. Their study participants wore opaque goggles in order to eliminate photostimulation of serotonin through the retino-raphe tract. The study showed that just 15-20 minutes of UVA exposure resulted in increased levels of serotonin in the blood.

Is this one of the reasons why sunbathing makes us feel good? Well, healthy levels of serotonin in the blood help to regulate many physiological functions, as shown in Figure 2 above. But serotonin can’t pass through the blood-brain barrier—this is why straight-up oral serotonin isn’t prescribed for depression. Instead, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are used to inhibit the reabsorption of serotonin by neurons in the brain, which increases circulating serotonin levels and improves mood.

However, rat experiments demonstrate how the serotonin transporter (SERT), which is present in the blood-brain barrier, may allow serotonin (5-HT) levels in the brain to affect levels in the body, and vice versa. The science of how this works is not completely understood yet. For now, if you want to increase your serotonin levels naturally, it’s probably best to address each area of synthesis—brain, skin, and gut—so that each area can produce the serotonin that it needs locally, and potentially all contribute to your overall health.

What happens when serotonin levels are low?

Since serotonin helps to regulate so many functions of our brain and body, lower than normal levels (serotonin deficiency) can cause or contribute to a wide range of symptoms. Higher than normal levels of serotonin are dangerous too; this is referred to as serotonin syndrome or toxicity, and it’s typically caused by taking medications that cause serotonin to build up in the body.

Symptoms of serotonin deficiency include:

- Seasonal or chronic depression

- Anxiety and worry

- Panic attacks

- Phobias, obsessions, and compulsive or impulsive behavior

- Low self-esteem

- Aggression and irritability

- Hyperactivity

- Insomnia and sleep cycle disturbances

- Irritable bowel and GI distress

- PMS and hormone dysfunction

- Weight gain and carbohydrate cravings

- Eating disorders

- Fatigue

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic pain and muscle pain

- Migraine headaches

- Poor memory and cognitive impairment

- Alcohol abuse

Serotonin helps to regulate virtually all aspects of human behavior, including mood, anger, aggression, reward, appetite, memory, perception, sexuality, attention, and more. This is why drugs targeting serotonergic activity and serotonin receptors in the central nervous system are prescribed or in development for the treatment of nearly every neuropsychiatric disorder.

Researchers have shown how bright light stimulates serotonin production through the retino-raphe tract, resulting in similar reduction of depressive behavior as SSRIs. They’ve also shown the reverse—that light deprivation produces depressive behavior. Serotonin production is one of the reasons why bright light therapy (BLT) is now used to treat seasonal and non-seasonal depression.

Depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and rates of completed suicide tend to increase during the winter months when people get less exposure to sunlight. Mood disorders are complex, but it’s clear that low serotonin levels play a role in these seasonal swings.

The relationship between neurotransmitters and mood is most often researched by examining how imbalanced levels of these chemicals affect mood. But researchers in Montreal did an interesting study to explore the opposite: how mood affects levels of serotonin. They asked study participants to recall memories in which they felt sad, happy, and neutral. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans showed that reported levels of happiness correlated with increased serotonin synthesis, and reported levels of sadness correlated with decreased serotonin synthesis. The participants’ self-induced moods directly affected their serotonin levels. This study suggests that the relationship between serotonin and mood may be two-way, with each affecting the other.

Of particular interest to the readers of this blog is how serotonin levels affect pain perception. Serotonin plays a fundamental role in pain perception in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Serotonin regulates pain information sent from peripheral nerve fibers to the spinal cord and brain, and helps to modulate the psychological perception of pain in the cortical and limbic regions of the brain. This is why serotonergic drugs can be effective in managing chronic pain disorders. For example, women with fibromyalgia have significantly low serum serotonin levels, which helps to explain their heightened pain sensation, related symptoms such as gastrointestinal and sleep issues, and positive response to SSRIs.

What is melatonin, and how do we produce it?

Melatonin is a hormone best known for regulating our sleep-wake cycle. It also functions as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory, and helps to regulate blood pressure and reproductive function.

Our brain produces melatonin in response to darkness—this is called “dim-light melatonin onset.” When our retinas detect darkness, a signal is sent through the retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic nuclei, a brain region that controls circadian rhythms. From there, a signal is sent to the pineal gland, a small endocrine gland in our brain (see diagram of the retino-raphe tract above) that produces melatonin. This is why dimming the lights in your house and avoiding the blue light of televisions is recommended before going to bed: blue light suppresses melatonin synthesis. While melatonin doesn’t actually make us fall asleep, it plays the essential role of letting our brain know that it’s time to go to sleep.

Serotonin is a melatonin precursor; the pineal gland uses serotonin to synthesize melatonin. The healthier our levels of serotonin, the more likely it is that we’ll have healthy levels of melatonin too.

When the pineal gland produces melatonin, it is then released into the bloodstream and distributed throughout the body. Research shows that melatonin reaches maximum levels between 2:00am and 4:00am in healthy individuals. As daylight approaches and our retinas detect increasing levels of light, melatonin levels fall. During the daytime, melatonin levels are low or undetectable.

In addition to the pineal gland, melatonin is produced throughout the body for local use. Photoreceptors of the retina produce melatonin to help protect the health and function of the eye. The gastrointestinal tract produces melatonin to regulate the health and function of the intestinal epithelium (gut lining), enhance the immune system of the gut, and relax the GI muscles. And melatonin produced by the skin protects against oxidative stress and ultraviolet radiation-induced damage to the skin.

What happens when melatonin levels are low?

As you would expect, melatonin deficiency or dysfunction is associated with circadian rhythm sleep disorders. These disorders typically involve difficulty falling asleep, frequent waking and inability to stay asleep, and waking up too early and not being able to fall back to sleep.

Low levels of melatonin play a role in stress and mood disorders as well. Low serotonin levels contribute to depressive symptoms and melatonin deficiency. The resulting lack of sleep contributes to increased levels of cortisol (a stress hormone) and depressive symptoms.

Melatonin secretion is altered in neurodegenerative conditions including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Production of the hormone also naturally decreases with age, and this decline in melatonin levels has been suggested to be one of the major causes of age-related neurodegeneration. In the central nervous system, melatonin regulates antioxidant and prooxidant enzymes, prevents damage caused by free radicals, promotes survival of neurons under increased oxidative stress, and prevents buildup and toxicity of amyloid plaques. Studies show that melatonin may slow progression of neurodegenerative diseases as well as improve sleep efficiency and cognitive function.

Melatonin deficiency weakens the immune system, making us more susceptible to viral and bacterial infections, autoimmune conditions, inflammation, and even cancer. Melatonin is an antioxidant and free radical scavenger, and plays an important role in our innate immune system, our first line of defense against attack. Melatonin can inhibit growth of cancerous tumors, and may help prevent breast cancer, prostate cancer, gastric cancer, and colorectal cancer. It also protects healthy cells from radiation-induced and chemotherapy-induced toxicity, so it can be used as an adjuvant of cancer therapies.

While we tend to be most aware of melatonin’s function in the brain—its effect on our sleep patterns—about 500 times more melatonin is produced in our gut than in our brain. As such, local melatonin deficiency may lead to health problems in the gastrointestinal tract. In the GI tract, melatonin acts as a free radical scavenger, reduces secretion of hydrochloric acid, stimulates the immune system, and increases microcirculation. It protects the mucosa (protective lining of the GI tract) against various irritants, and heals lesions including stomatitis, esophagitis, gastritis, and peptic ulcers. Because of its many benefits, researchers suggest that melatonin can be used for prevention or treatment of colorectal cancer, ulcerative colitis, gastric ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, and childhood colic.

How to boost your serotonin and melatonin levels naturally

If you want to improve your mood, regulate your pain perception, regulate your sleep cycle and improve your sleep quality, boosting your brain’s production of serotonin and melatonin should be at the top of your list. And by now you know the best way to do it—go outside!

Timing is important: Being exposed to natural light in the morning—without sunglasses—advances our circadian clock, stimulating melatonin production earlier in the evening and making it easier to fall asleep at night. Daylight exposure later in the day has not been shown to have the same positive effects on circadian rhythms. In addition to regulating our sleep-wake cycle, our circadian rhythms also regulate hormone production, appetite, core body temperature, brain wave activity, and cell regeneration. Keeping our circadian clock properly set is important for our overall health.

How much time should you spend outdoors? Well, consider that humans evolved living completely outdoors, so the systems of our brains and bodies are built to function best with a lot of natural light. And until relatively recently, much of the world’s population was involved in farming and spent much of the day outdoors. The shift to indoor living is recent, and it’s a big contributor to chronic disease. Most of us live our lives deprived of the bright, natural light that is essential for our health. So, the more the better, as long as you take steps to protect against skin cancer.

Since we’ve depleted the ozone layer, we’re exposed to more ultraviolet rays, increasing our risk of skin cancer. However, this does not mean you should avoid the sun completely—it’s all about moderation. Protect your skin and avoid long periods of time in direct sunlight, especially during midday when sunlight is most intense. And remember, you can sit in the shade while still exposing your eyes to daylight, which is critical for serotonin production.

Another way to boost serotonin levels is with exercise. Exercise increases levels of tryptophan (the precursor to serotonin) in the brain, and these elevated levels persist after exercise. Exercise also increases the firing rate of serotonin neurons, resulting in an increase in release and synthesis of serotonin.

Wrap up your day by dimming the lights in your house in the evening before bed. Once you get in bed, avoid watching television or looking at mobile devices; their blue light will inhibit melatonin production. Instead, read a book or let one of the many free guided meditations on YouTube lull you to sleep.

If you spend much of the day indoors, find ways to make getting outside part of your regular routine. Get in touch with your primal need for daylight and darkness and their effects on your biological rhythms. Your brain and body will thank you for it!

Recommended reading:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna