¿Por qué dormimos y cuáles son los peligros de no dormir lo suficiente?

I just finished reading the New York Times bestseller Por qué dormimos by neuroscientist Matthew Walker, and it was fantastic. Sleep is essential for all aspects of health—from maintaining immune system, cardiovascular, and reproductive function to improving memory and preventing cancer, psychiatric disorders, and neurodegenerative decline. Yet the importance of sleep is vastly under-recognized, and we’re paying the price.

A National Sleep Foundation survey found that in the US, Canada, UK, Germany, and Japan, at least 50% of people don’t get sufficient sleep on weekdays. For most people, that means less than 7 hours. If you lead a busy life and routinely get 5 to 6 hours of sleep, you may feel pretty good about that. Unfortunately, studies consistently show the negative health effects of regularly sleeping 6 or fewer hours per night. And as Walker explains in his book, trying to catch up on sleep on the weekends doesn’t work; the damage has already been done.

If you think you’re one of those people who can function optimally on less sleep than the rest of us—you’re probably not. Less than 1% of people carry a gene, DEC2, which allows them to survive on less than five to six hours of sleep and experience minimal impairment in functioning. Walker writes that it is far more likely that you’ll be struck by lightning than have this gene.

Walker discusses every aspect of sleep you can think of in his outstanding book. His readable writing style and British wit made it hard for me to put down. In this post I’ll highlight some of the most important things I learned from the book. If you want to learn more, or if you need any further motivation to get a good night’s sleep, I highly recommend reading Por qué dormimos.

Sueño REM vs NREM, y por qué necesitamos ambos

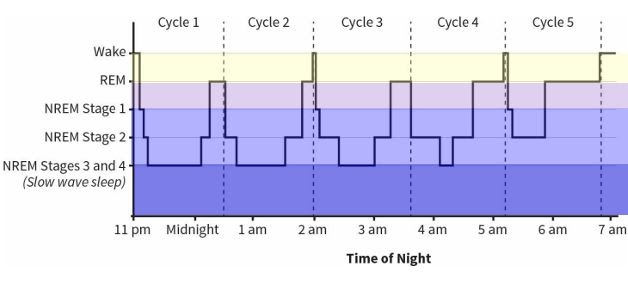

El sueño con movimientos oculares no rápidos, conocido como sueño NREM, se caracteriza por nuestras ondas cerebrales más lentas. Por el contrario, durante el sueño de movimientos oculares rápidos (REM), la actividad cerebral es casi idéntica a cuando estamos despiertos. Pasamos por el sueño REM y las cuatro etapas del sueño NREM aproximadamente cada 90 minutos durante la noche.

Figure 8: The Architecture of Sleep from Por qué dormimos

Los científicos están de acuerdo en que el sueño NREM apareció primero en la evolución. Los estudios del sueño en insectos, anfibios, peces y la mayoría de los reptiles no muestran evidencia concreta de sueño REM. Las aves y los mamíferos, que evolucionaron más tarde, son las únicas especies que exhiben un verdadero sueño REM.

El sueño REM es cuando soñamos. Aquí es cuando nuestro cerebro toma toda la información que hemos recibido durante el día y la procesa, integrándola con nuestras experiencias pasadas. Al hacerlo, el sueño REM crea redes asociativas en todo nuestro cerebro, construyendo un marco para comprender nuestra vida y el mundo que nos rodea, y brindándonos conocimientos y la capacidad de resolver problemas.

Dreaming is also essential for processing emotions and regulating emotional circuits. Studies by Dr. Rosalind Cartwright have shown how dreaming about traumatic events that we’ve experienced allows us to process and move past them, resulting in recovery from depression and anxiety. And research by Dr. Murray Raskind showed that reducing noradrenaline in the brain allowed PTSD patients to finally obtain REM sleep, which resulted in their flashbacks ceasing.

By contrast, in NREM sleep, we do not dream. NREM sleep is when our brains store and strengthen the memories of what we learned—this is known as memory consolidation. Not surprisingly, lack of memory consolidation is one of the two reasons that inadequate NREM sleep is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The other reason is fascinating: Dr. Maiken Nedergaard discovered that during NREM sleep, glial cells (the brain’s support cells) shrink by up to 60%, and cerebrospinal fluid bathes the brain, clearing out metabolic debris. If this cleansing doesn’t occur, wastes including amyloid protein, tau protein, and other toxic metabolites build up in the brain, contributing to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

NREM sleep also plays an essential role in the maturation of the brain during adolescence and into adulthood. Knowing this, we ought to make sleep a priority for our teenagers—but unfortunately, we’re often misinformed about how best to do this, and school schedules don’t help. During adolescence, circadian rhythms shift several hours later; so, teens don’t naturally get tired until around 11:00pm. They need more sleep than adults—on average, 9.25 hours—and their brains produce melatonin from 11:00pm to 8:00am. Unfortunately, most high schools start between 7:00 and 8:00am, when teens should still be in bed.

When Edina, Minnesota shifted their high school start time from 7:20am to 8:30am, it resulted in a dramatic increase in SAT scores. The average score among top-performing students went from 605 to 761 on the verbal portion of the test, and from 683 to 739 on the math portion. Attendance and graduation rates went up significantly, students reported less depression, school nurses reported better student health, and 92% of parents reported that their teens were easier to live with. Similar results have been reported in other counties and states where school start times have been shifted later.

(If you’re looking for guidance on sleep patterns for infants and children, I highly recommend Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child by Dr. Marc Weissbluth.)

¿Cuánto y cuándo deben dormir los adultos para tener una salud óptima?

Walker explains that adults need an average of 8 hours of sleep per night to maintain optimal health. Other sources such as the National Sleep Foundation, The American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and the Sleep Research Society recommend between 7 and 9 hours or at least 7 hours per night.

Estaba muy interesado en saber que los humanos están biológicamente programados para dormir en un patrón bifásico, en lugar del patrón monofásico al que la mayoría de nosotros nos adherimos. El sueño monofásico es cuando intentamos dormir todo en un tramo largo. El sueño bifásico significa que tenemos dos períodos de sueño en un día de 24 horas. Todos los seres humanos experimentan un "descenso genéticamente programado en el estado de alerta" a media tarde, llamado "descenso del estado de alerta posprandial". Funcionamos mejor cuando tomamos una siesta corta, de 30 a 60 minutos de duración, durante este período de la tarde. Entonces deberíamos dormir el resto de nuestro sueño durante la noche.

Some cultures in Mediterranean Europe and South America still allow for an afternoon siesta in their daily schedule. Sadly, when the afternoon nap is removed, there can be dire health consequences. Researchers from Harvard University’s School of Public Health followed more than 23,000 Greek adults over a six-year period, during which the practice of siesta was coming to an end for some of them. The researchers found that people who continued to take afternoon naps had a 37% lower risk of death from heart disease than those who did not take naps. Working men in particular benefited from an afternoon nap, showing a 60% reduced risk of death from heart disease.

Walker recomienda tomar la siesta a primera hora de la tarde en lugar de al final de la tarde o la noche. La siesta elimina la "presión del sueño" creada por la acumulación de adenosina (que explicaré en la siguiente sección), por lo que tomar una siesta más tarde en el día hace que sea más difícil conciliar el sueño por la noche.

Cómo la cafeína y el alcohol afectan nuestro sueño

Después de haber bebido café durante 23 años y haber dejado de fumar recientemente, estaba muy interesado en saber exactamente por qué la cafeína nos ayuda a sentirnos alerta y con energía.

Desde el momento en que nos despertamos y durante el día, una sustancia química llamada adenosina se acumula continuamente en nuestros cerebros. La adenosina crea el deseo de dormir. Cuanto más tiempo estamos despiertos, más adenosina se acumula y más presión del sueño sentimos.

La cafeína se adhiere a los receptores de adenosina en el cerebro, bloqueando las señales de sueño que la adenosina está tratando de enviar al cerebro. Es por eso que la cafeína nos hace sentir despiertos, durante un período de tiempo. Pero mientras experimentamos el maravilloso subidón de la cafeína, la adenosina continúa acumulándose. A medida que nuestros cuerpos metabolizan la cafeína y sus efectos desaparecen, experimentamos un choque de cafeína. De repente, se sienten los efectos de toda la adenosina que ha seguido acumulándose.

Durante la noche, mientras dormimos, nuestro cerebro se degrada y elimina la adenosina que se ha acumulado durante el día. Si dormimos aproximadamente 8 horas, podemos eliminar por completo la adenosina de nuestro cerebro, lo que nos permite sentirnos alerta por la mañana.

The half-life of caffeine, which is the length of time it takes our bodies to metabolize and clear away half of the dose of caffeine we’ve ingested, is approximately 5 hours. However, this length of time varies widely among individuals, ranging from 1.5 to 9.5 hours. This variance explains why some people can drink coffee right before bed and still fall asleep soundly, whereas others, like myself, are kept awake at night by a cup of coffee at lunchtime.

Consumir cafeína hasta el punto de afectar su sueño por la noche es peligroso, porque es muy fácil entrar en un ciclo en el que nunca duerme lo suficiente como para eliminar por completo la adenosina de su cerebro. Como yo y muchos otros hemos experimentado, esto conduce rápidamente a la dependencia de la cafeína. Si eres una persona promedio y tu cuerpo elimina el 50% de cafeína de tu sistema en 5 horas, ten en cuenta que media dosis de cafeína es suficiente para mantenerte despierto por la noche. Otras 5 horas después, el cuarto de dosis de cafeína que queda en su sistema es suficiente para afectar su sueño también.

Ahora pasemos al alcohol, que muchas personas creen que les ayuda a dormir mejor. Si bien el alcohol es un sedante que ralentiza la activación de las neuronas en el cerebro, no induce el sueño natural. Walker explica que su efecto sobre la actividad cerebral es más parecido a una dosis ligera de anestesia.

Sleep studies show that when we go to bed with alcohol in our system, the second half of our night of sleep is significantly disrupted. We briefly wake up many times, so our sleep is not continuous and not restorative. Most people don’t remember these awakenings, so they don’t realize that their evening drink is the cause of their grogginess the next morning. These disruptions during the second half of the night also result in a loss of important REM sleep.

Alcohol, even in moderate consumption, is a powerful suppressor of REM sleep. Walker describes a study of college students that clearly showed the negative effect of alcohol and the resulting loss of REM sleep on retention of academic material they had just learned. When students drank a moderate amount of alcohol on the first night after they had learned the new material, they only retained 50% of the information as compared to the control group, who did not drink. But more surprising was the result of a third group of students, who had two nights of natural, sober sleep after learning the new material. On the third night, they drank a moderate amount of alcohol. They then experienced a 40% loss of the new material they had learned 3 days before—almost as much as the students who had drank on the first night.

Los efectos sobre la salud de la privación crónica del sueño

La pérdida crónica de sueño, que resulta de dormir menos de 6 a 7 horas de forma regular, está asociada con una amplia gama de condiciones.

-

It weakens the immune system: People who sleep 6 hours or less per night are 4 times more likely to catch a cold than those who sleep at least 7 hours per night

-

It increases the risk of cancer: Walker describes a European study of almost 25,000 people which found that sleeping six hours or less per night was associated with a 40% increased risk of cancer, compared to people who slept 7 hours or more per night. Other studies have found a 50% increased risk of colorectal cancer, a 62% increased risk of breast cancer, and a 90% increased risk of prostate cancer among people who sleep 6 or fewer hours per night. And just one night of only 4 hours of sleep results in a loss of 72% of the natural killer cells of the immune system���our first line of defense against dangerous invaders such as cancer cells.

-

It leads to cognitive decline: People with insomnia are more than twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease And in healthy adults, chronic sleep deprivation causes parts of the brain involved in learning and memory to shrink and their short-term memory to be impaired.

-

It affects fertility: Men who experience sleep disturbances have a 29% lower sperm count, and women who get less than 6 hours of sleep per night have 20% less follicular-releasing hormone, than those who get regular, full nights of sleep. And sleep-deprived men have significantly lower testosterone levels, equivalent to aging 10 to 15 years, while sleep-deprived women are more likely to have irregular menstrual cycles and experience infertility.

-

It increases the risk of cardiovascular disease: A 2011 study that tracked more than half a million people across 8 countries found that getting less sleep was associated with a 45% increased risk of developing or dying from coronary heart disease, independent of other lifestyle factors. A Japanese study of 4,000 men found an alarming 400-500% increased risk of heart attack among men who slept six hours or less as compared to men who slept more than six hours. Sleep loss makes the sympathetic nervous system overactive, resulting in an immediate increase in heart rate and blood pressure, weakened blood vessels, and a 200-300% increased risk of atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

-

It increases the risk of diabetes: Research shows that after just 6 days of sleeping 4 hours per night, previously healthy volunteers develop pre-diabetic blood sugar levels; their cells become insulin-resistant after just one week of sleep loss.

-

It increases appetite and leads to weight gain: Sleep loss immediately leads to a decrease in leptin (the hormone that makes us feel full) and an increase in ghrelin (the hormone that makes us feel hungry), making sleep-deprived people consume more calories than those who get sufficient sleep. Sleep loss also increases levels of endocannabinoids in the body, giving us “the munchies” and making us more likely to snack.

-

It increases emotional reactivity and risk of psychiatric disorders and substance abuse: After just one night of sleep deprivation, the amygdala (a part of the brain central to stress and strong emotions) becomes more than 60% more reactive, and the prefrontal cortex (which helps to regulate the amygdala) becomes less active. After just three nights of restricted REM sleep, people become anxious, moody, paranoid, and have hallucinations. Sleep loss also makes the brain’s reward system hyperactive, leading people to pursue pleasure in the form of drugs and alcohol.

¿Qué debe hacer si tiene insomnio?

Los investigadores han determinado que el insomnio, que se define como tener la oportunidad de dormir pero no poder conciliar el sueño y / o permanecer dormido, es causado más comúnmente por preocupaciones emocionales y estrés psicológico. Si tiene insomnio, probablemente esto no sea una sorpresa. Cuando está despierto en la cama por la noche con la mente acelerada, sabe que solo necesita dejar que su mente se relaje y se relaje para poder conciliar el sueño, pero permitir que eso suceda puede ser un desafío o imposible.

Los escáneres cerebrales de las personas que padecen insomnio muestran que las regiones del cerebro que generan emociones, recuerdan recuerdos y mantienen la vigilancia permanecen activas mientras intentan conciliar el sueño, lo que evita la aparición del sueño. Y cuando se duermen, los que sufren de insomnio tienen un sueño NREM superficial y un sueño REM fragmentado, lo que los lleva a no sentirse descansados al día siguiente.

La melatonina es una opción atractiva porque es natural y no tiene los efectos secundarios de los somníferos recetados. Walker explica que la melatonina ayuda a regular el momento en que se produce el sueño, pero en realidad no genera sueño. Él cree que la melatonina es más útil cuando se trata de jet lag y tener que adaptarse a una nueva zona horaria. También advierte que las píldoras de melatonina de venta libre pueden tener concentraciones de melatonina mucho más altas o más bajas que las anunciadas. Pero por el lado positivo, Walker sugiere que el efecto placebo de la melatonina es significativo y no debe subestimarse.

Walker does not recommend prescription sleeping pills, and he makes a clear case for why. Sleeping pills are sedatives, just as alcohol is, and they have the same effect: they slow neuronal firing and basically knock out higher regions of the brain. They do not induce natural sleep, and they also lead to grogginess the following day, forgetfulness, slowed reaction times, and performing actions at night that you do not remember the next day. The grogginess can lead people to become increasingly dependent on caffeine, making the sleeping pills more necessary. And when people stop taking sleeping pills, they often suffer from rebound insomnia as they withdraw from the addictive drugs. People who regularly take sleeping pills are 3.6 to 5.3 times more likely to die than those who don’t; the most common causes are infection, fatal car accidents, and cancer.

Non-pharmacological treatments for sleep are becoming more popular, and one in particular has proven to be more effective than drugs. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown in many clinical studies to be more effective than prescription sleep aids in helping people to fall asleep faster, sleep longer, and get better quality sleep. The effects of CBT-I are long-term and persist after treatment has ended. And best of all, there are no dangerous side effects.

The efficacy of CBT-I is so undeniable that in 2016, the American College of Physicians declared that CBT-I should be used as the first-line treatment for all individuals suffering from insomnia, not sleeping pills. You can learn more about CBT-I in this article on the Sleep Foundation website, and by searching for a CBT-I trained provider near you.

¿Querer aprender más?

Todavía hay cosas más fascinantes que aprender en el libro de Walker: cómo evolucionaron nuestros ciclos de sueño, los peligros de conducir con falta de sueño, cómo dos catástrofes globales fueron causadas por la falta de sueño, cómo la tecnología puede mejorar nuestro sueño, por qué Walker cree que dormir es más importante para nuestra salud que la dieta y el ejercicio, y sus 12 consejos para un sueño saludable.

If you want to learn more about why we sleep and the dangers of not getting enough sleep, or if you still need motivation to get a good night’s sleep, I highly recommend reading Por qué dormimos!

Lectura recomendada:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna