Pourquoi dormons-nous et quels sont les dangers de ne pas en avoir assez ?

I just finished reading the New York Times bestseller Pourquoi nous dormons by neuroscientist Matthew Walker, and it was fantastic. Sleep is essential for all aspects of health—from maintaining immune system, cardiovascular, and reproductive function to improving memory and preventing cancer, psychiatric disorders, and neurodegenerative decline. Yet the importance of sleep is vastly under-recognized, and we’re paying the price.

A National Sleep Foundation survey found that in the US, Canada, UK, Germany, and Japan, at least 50% of people don’t get sufficient sleep on weekdays. For most people, that means less than 7 hours. If you lead a busy life and routinely get 5 to 6 hours of sleep, you may feel pretty good about that. Unfortunately, studies consistently show the negative health effects of regularly sleeping 6 or fewer hours per night. And as Walker explains in his book, trying to catch up on sleep on the weekends doesn’t work; the damage has already been done.

If you think you’re one of those people who can function optimally on less sleep than the rest of us—you’re probably not. Less than 1% of people carry a gene, DEC2, which allows them to survive on less than five to six hours of sleep and experience minimal impairment in functioning. Walker writes that it is far more likely that you’ll be struck by lightning than have this gene.

Walker discusses every aspect of sleep you can think of in his outstanding book. His readable writing style and British wit made it hard for me to put down. In this post I’ll highlight some of the most important things I learned from the book. If you want to learn more, or if you need any further motivation to get a good night’s sleep, I highly recommend reading Pourquoi nous dormons.

Sommeil REM vs sommeil NREM, et pourquoi nous avons besoin des deux

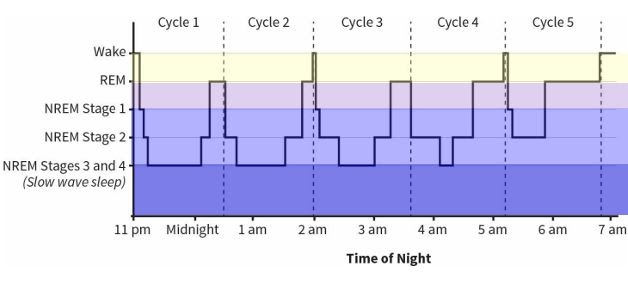

Le sommeil à mouvements oculaires non rapides, appelé sommeil NREM, est caractérisé par nos ondes cérébrales les plus lentes. En revanche, pendant le sommeil à mouvements oculaires rapides (REM), l'activité cérébrale est presque identique à celle de l'éveil. Nous parcourons le sommeil paradoxal et quatre phases de sommeil NREM environ toutes les 90 minutes tout au long de la nuit.

Figure 8: The Architecture of Sleep from Pourquoi nous dormons

Les scientifiques s'accordent à dire que le sommeil NREM est apparu en premier dans l'évolution. Les études du sommeil sur les insectes, les amphibiens, les poissons et la plupart des reptiles ne montrent pas de preuves concrètes du sommeil paradoxal. Les oiseaux et les mammifères, qui ont évolué plus tard, sont les seules espèces qui présentent un véritable sommeil paradoxal.

Le sommeil paradoxal, c'est quand nous rêvons. C'est à ce moment que notre cerveau prend toutes les informations que nous avons reçues au cours de la journée et les traite, en les intégrant à nos expériences passées. Ce faisant, le sommeil paradoxal crée des réseaux associatifs dans tout notre cerveau, construisant un cadre pour comprendre notre vie et le monde qui nous entoure. us, et donner us perspicacité et capacité à résoudre des problèmes.

Dreaming is also essential for processing emotions and regulating emotional circuits. Studies by Dr. Rosalind Cartwright have shown how dreaming about traumatic events that we’ve experienced allows us to process and move past them, resulting in recovery from depression and anxiety. And research by Dr. Murray Raskind showed that reducing noradrenaline in the brain allowed PTSD patients to finally obtain REM sleep, which resulted in their flashbacks ceasing.

By contrast, in NREM sleep, we do not dream. NREM sleep is when our brains store and strengthen the memories of what we learned—this is known as memory consolidation. Not surprisingly, lack of memory consolidation is one of the two reasons that inadequate NREM sleep is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The other reason is fascinating: Dr. Maiken Nedergaard discovered that during NREM sleep, glial cells (the brain’s support cells) shrink by up to 60%, and cerebrospinal fluid bathes the brain, clearing out metabolic debris. If this cleansing doesn’t occur, wastes including amyloid protein, tau protein, and other toxic metabolites build up in the brain, contributing to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

NREM sleep also plays an essential role in the maturation of the brain during adolescence and into adulthood. Knowing this, we ought to make sleep a priority for our teenagers—but unfortunately, we’re often misinformed about how best to do this, and school schedules don’t help. During adolescence, circadian rhythms shift several hours later; so, teens don’t naturally get tired until around 11:00pm. They need more sleep than adults—on average, 9.25 hours—and their brains produce melatonin from 11:00pm to 8:00am. Unfortunately, most high schools start between 7:00 and 8:00am, when teens should still be in bed.

When Edina, Minnesota shifted their high school start time from 7:20am to 8:30am, it resulted in a dramatic increase in SAT scores. The average score among top-performing students went from 605 to 761 on the verbal portion of the test, and from 683 to 739 on the math portion. Attendance and graduation rates went up significantly, students reported less depression, school nurses reported better student health, and 92% of parents reported that their teens were easier to live with. Similar results have been reported in other counties and states where school start times have been shifted later.

(If you’re looking for guidance on sleep patterns for infants and children, I highly recommend Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child by Dr. Marc Weissbluth.)

Combien et quand les adultes devraient-ils dormir pour une santé optimale ?

Walker explains that adults need an average of 8 hours of sleep per night to maintain optimal health. Other sources such as the National Sleep Foundation, The American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and the Sleep Research Society recommend between 7 and 9 hours or at least 7 hours per night.

J'ai été très intéressé d'apprendre que les humains sont biologiquement câblés pour dormir selon un schéma biphasique, plutôt que le schéma monophasique que la plupart des us adhérer à. Le sommeil monophasique, c'est quand nous essayons d'obtenir tout notre sommeil en une seule longue période. Le sommeil biphasique signifie que nous avons deux périodes de sommeil dans une journée de 24 heures. Tous les humains connaissent une «baisse de vigilance génétiquement câblée» au milieu de l'après-midi, appelée «baisse de vigilance post-prandiale». Nous fonctionnons mieux lorsque nous faisons une courte sieste, de 30 à 60 minutes, pendant cette période de l'après-midi. Nous devrions ensuite obtenir le reste de notre sommeil pendant la nuit.

Some cultures in Mediterranean Europe and South America still allow for an afternoon siesta in their daily schedule. Sadly, when the afternoon nap is removed, there can be dire health consequences. Researchers from Harvard University’s School of Public Health followed more than 23,000 Greek adults over a six-year period, during which the practice of siesta was coming to an end for some of them. The researchers found that people who continued to take afternoon naps had a 37% lower risk of death from heart disease than those who did not take naps. Working men in particular benefited from an afternoon nap, showing a 60% reduced risk of death from heart disease.

Walker recommande de faire la sieste en début d'après-midi plutôt qu'en fin d'après-midi ou en soirée. La sieste élimine la «pression du sommeil» créée par l'accumulation d'adénosine (que j'expliquerai dans la section suivante), donc faire une sieste plus tard dans la journée rend plus difficile l'endormissement la nuit.

Comment la caféine et l'alcool affectent notre sommeil

Ayant été un buveur de café pendant 23 ans et ayant récemment arrêté, j'étais très intéressé de savoir exactement pourquoi la caféine aide us se sentir alerte et plein d'énergie.

À partir du moment où nous nous réveillons et tout au long de la journée, une substance chimique appelée adénosine s'accumule continuellement dans notre cerveau. L'adénosine crée le désir de dormir. Plus nous sommes éveillés longtemps, plus l'adénosine s'accumule et plus nous ressentons la pression du sommeil.

La caféine se fixe sur les récepteurs de l'adénosine dans le cerveau, bloquant les signaux de sommeil que l'adénosine essaie d'envoyer au cerveau. C'est pourquoi la caféine rend us se sentir éveillé pendant un certain temps. Mais pendant que nous vivons le merveilleux high de la caféine, l'adénosine continue de s'accumuler. Au fur et à mesure que notre corps métabolise la caféine et que ses effets s'estompent, nous subissons un crash de caféine. Les effets de toute l'adénosine qui a continué à s'accumuler se font soudainement sentir.

Pendant la nuit pendant que nous dormons, notre cerveau se dégrade et élimine l'adénosine qui s'est accumulée tout au long de la journée. Si nous dormons environ 8 heures, nous sommes capables d'éliminer complètement l'adénosine de notre cerveau, permettant us se sentir alerte le matin.

The half-life of caffeine, which is the length of time it takes our bodies to metabolize and clear away half of the dose of caffeine we’ve ingested, is approximately 5 hours. However, this length of time varies widely among individuals, ranging from 1.5 to 9.5 hours. This variance explains why some people can drink coffee right before bed and still fall asleep soundly, whereas others, like myself, are kept awake at night by a cup of coffee at lunchtime.

Consommer de la caféine au point d'affecter votre sommeil la nuit est dangereux, car il est trop facile d'entrer dans un cycle où vous n'obtenez jamais assez de sommeil de qualité pour éliminer complètement l'adénosine de votre cerveau. Comme beaucoup d'autres et moi-même en avons fait l'expérience, cela conduit rapidement à une dépendance à la caféine. Si vous êtes une personne moyenne et que votre corps élimine 50 % de la caféine de votre système en 5 heures, n'oubliez pas qu'une demi-dose de caféine suffit à vous empêcher de dormir la nuit. Encore 5 heures plus tard, le quart de dose de caféine qui reste dans votre système suffit également à affecter votre sommeil.

Passons maintenant à l'alcool, qui, selon de nombreuses personnes, les aide à mieux dormir. Alors que l'alcool est un sédatif, ralentissant le déclenchement des neurones dans le cerveau, il n'induit pas le sommeil naturel. Walker explique que son effet sur l'activité cérébrale ressemble plus à une légère dose d'anesthésie.

Sleep studies show that when we go to bed with alcohol in our system, the second half of our night of sleep is significantly disrupted. We briefly wake up many times, so our sleep is not continuous and not restorative. Most people don’t remember these awakenings, so they don’t realize that their evening drink is the cause of their grogginess the next morning. These disruptions during the second half of the night also result in a loss of important REM sleep.

Alcohol, even in moderate consumption, is a powerful suppressor of REM sleep. Walker describes a study of college students that clearly showed the negative effect of alcohol and the resulting loss of REM sleep on retention of academic material they had just learned. When students drank a moderate amount of alcohol on the first night after they had learned the new material, they only retained 50% of the information as compared to the control group, who did not drink. But more surprising was the result of a third group of students, who had two nights of natural, sober sleep after learning the new material. On the third night, they drank a moderate amount of alcohol. They then experienced a 40% loss of the new material they had learned 3 days before—almost as much as the students who had drank on the first night.

Les effets sur la santé de la privation chronique de sommeil

La perte de sommeil chronique, qui résulte d'un sommeil régulier de moins de 6 à 7 heures, est associée à un large éventail de conditions.

-

It weakens the immune system: People who sleep 6 hours or less per night are 4 times more likely to catch a cold than those who sleep at least 7 hours per night

-

It increases the risk of cancer: Walker describes a European study of almost 25,000 people which found that sleeping six hours or less per night was associated with a 40% increased risk of cancer, compared to people who slept 7 hours or more per night. Other studies have found a 50% increased risk of colorectal cancer, a 62% increased risk of breast cancer, and a 90% increased risk of prostate cancer among people who sleep 6 or fewer hours per night. And just one night of only 4 hours of sleep results in a loss of 72% of the natural killer cells of the immune system—our first line of defense against dangerous invaders such as cancer cells.

-

It leads to cognitive decline: People with insomnia are more than twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease And in healthy adults, chronic sleep deprivation causes parts of the brain involved in learning and memory to shrink and their short-term memory to be impaired.

-

It affects fertility: Men who experience sleep disturbances have a 29% lower sperm count, and women who get less than 6 hours of sleep per night have 20% less follicular-releasing hormone, than those who get regular, full nights of sleep. And sleep-deprived men have significantly lower testosterone levels, equivalent to aging 10 to 15 years, while sleep-deprived women are more likely to have irregular menstrual cycles and experience infertility.

-

It increases the risk of cardiovascular disease: A 2011 study that tracked more than half a million people across 8 countries found that getting less sleep was associated with a 45% increased risk of developing or dying from coronary heart disease, independent of other lifestyle factors. A Japanese study of 4,000 men found an alarming 400-500% increased risk of heart attack among men who slept six hours or less as compared to men who slept more than six hours. Sleep loss makes the sympathetic nervous system overactive, resulting in an immediate increase in heart rate and blood pressure, weakened blood vessels, and a 200-300% increased risk of atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

-

It increases the risk of diabetes: Research shows that after just 6 days of sleeping 4 hours per night, previously healthy volunteers develop pre-diabetic blood sugar levels; their cells become insulin-resistant after just one week of sleep loss.

-

It increases appetite and leads to weight gain: Sleep loss immediately leads to a decrease in leptin (the hormone that makes us feel full) and an increase in ghrelin (the hormone that makes us feel hungry), making sleep-deprived people consume more calories than those who get sufficient sleep. Sleep loss also increases levels of endocannabinoids in the body, giving us “the munchies” and making us more likely to snack.

-

It increases emotional reactivity and risk of psychiatric disorders and substance abuse: After just one night of sleep deprivation, the amygdala (a part of the brain central to stress and strong emotions) becomes more than 60% more reactive, and the prefrontal cortex (which helps to regulate the amygdala) becomes less active. After just three nights of restricted REM sleep, people become anxious, moody, paranoid, and have hallucinations. Sleep loss also makes the brain’s reward system hyperactive, leading people to pursue pleasure in the form of drugs and alcohol.

Que faire si vous souffrez d'insomnie ?

Les chercheurs ont déterminé que l'insomnie - définie comme le fait d'avoir la possibilité de dormir mais d'être incapable de s'endormir et/ou de rester endormi - est le plus souvent causée par des préoccupations émotionnelles et un stress psychologique. Si vous souffrez d'insomnie, cela n'est probablement pas une surprise. Lorsque vous êtes allongé éveillé dans votre lit la nuit avec votre esprit qui s'emballe, vous savez qu'il vous suffit de laisser votre esprit ralentir et de vous détendre pour pouvoir vous endormir, mais permettre que cela se produise peut être difficile, voire impossible.

Les scintigraphies cérébrales de personnes souffrant d'insomnie montrent que les régions du cerveau qui génèrent des émotions, rappellent des souvenirs et maintiennent la vigilance restent toutes actives tout en essayant de s'endormir, empêchant ainsi l'apparition du sommeil. Et lorsqu'ils s'endorment, les personnes souffrant d'insomnie ont un sommeil NREM peu profond et un sommeil REM fragmenté, ce qui les amène à ne pas se sentir reposées le lendemain.

La mélatonine est une option attrayante car elle est naturelle et exempte des effets secondaires des somnifères sur ordonnance. Walker explique que la mélatonine aide à réguler le moment où le sommeil se produit, mais ne génère pas réellement de sommeil. Il croit que la mélatonine est plus utile lorsqu'il s'agit de traiter le décalage horaire et de devoir s'adapter à un nouveau fuseau horaire. Il avertit également que les pilules de mélatonine en vente libre peuvent avoir des concentrations de mélatonine réelle beaucoup plus élevées ou plus faibles que celles annoncées. Mais du côté positif, Walker suggère que l'effet placebo de la mélatonine est important et ne doit pas être sous-estimé.

Walker does not recommend prescription sleeping pills, and he makes a clear case for why. Sleeping pills are sedatives, just as alcohol is, and they have the same effect: they slow neuronal firing and basically knock out higher regions of the brain. They do not induce natural sleep, and they also lead to grogginess the following day, forgetfulness, slowed reaction times, and performing actions at night that you do not remember the next day. The grogginess can lead people to become increasingly dependent on caffeine, making the sleeping pills more necessary. And when people stop taking sleeping pills, they often suffer from rebound insomnia as they withdraw from the addictive drugs. People who regularly take sleeping pills are 3.6 to 5.3 times more likely to die than those who don’t; the most common causes are infection, fatal car accidents, and cancer.

Non-pharmacological treatments for sleep are becoming more popular, and one in particular has proven to be more effective than drugs. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown in many clinical studies to be more effective than prescription sleep aids in helping people to fall asleep faster, sleep longer, and get better quality sleep. The effects of CBT-I are long-term and persist after treatment has ended. And best of all, there are no dangerous side effects.

The efficacy of CBT-I is so undeniable that in 2016, the American College of Physicians declared that CBT-I should be used as the first-line treatment for all individuals suffering from insomnia, not sleeping pills. You can learn more about CBT-I in this article on the Sleep Foundation website, and by searching for a CBT-I trained provider near you.

Voulez-vous en savoir plus?

Il y a encore des choses plus fascinantes à apprendre dans le livre de Walker : comment nos cycles de sommeil ont évolué, les dangers de conduire en manque de sommeil, comment deux catastrophes mondiales ont été causées par le manque de sommeil, comment la technologie peut améliorer notre sommeil, pourquoi Walker croit que le sommeil est plus important pour notre santé que l'alimentation et l'exercice, et ses 12 conseils pour un sommeil sain.

If you want to learn more about why we sleep and the dangers of not getting enough sleep, or if you still need motivation to get a good night’s sleep, I highly recommend reading Pourquoi nous dormons!

Lecture recommandée:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna