La Causa de la Escoliosis Idiopática:

Contracción Muscular Involuntaria

La escoliosis es considerada misteriosa e incurable por muchas personas en la comunidad médica. Si bien algunos casos de escoliosis son causados por anomalías estructurales congénitas o enfermedades neurológicas o musculares, la gran mayoría (alrededor del 85%) son de causa desconocida.

The fact is, the bones in our body do not move unless our muscles move them. And our muscles are controlled by our nervous system. So when our vertebrae move out of alignment in any way, they are being moved by our muscles, which are being controlled by our nervous system.

Many cases of idiopathic scoliosis are caused by chronically tight muscles pulling the spine out of alignment. If you have idiopathic scoliosis, you can touch your back and waist and feel how tight your muscles are.

Si su sistema nervioso envía mensajes a sus músculos para que se mantengan tensos, ninguna cantidad de alargamiento pasivo (como estiramiento estático o masaje) o realineación forzada (como corsé o quiropráctica) cambiará estos mensajes.

In this post, we’ll talk about the patterns of muscular contraction that are common in idiopathic scoliosis, how our natural motor learning process leads us to develop these patterns, and how pandiculation retrains the nervous system to release chronic, involuntary muscular contraction.

“This is the best program I have encountered. I am a military veteran, with 2 tours to Afghanistan and have scoliosis which became much worse due to all the heavy lifting and carry overseas. These exercises have released the muscles and I am almost back to normal.”

-Alisa

¿Qué es la escoliosis?

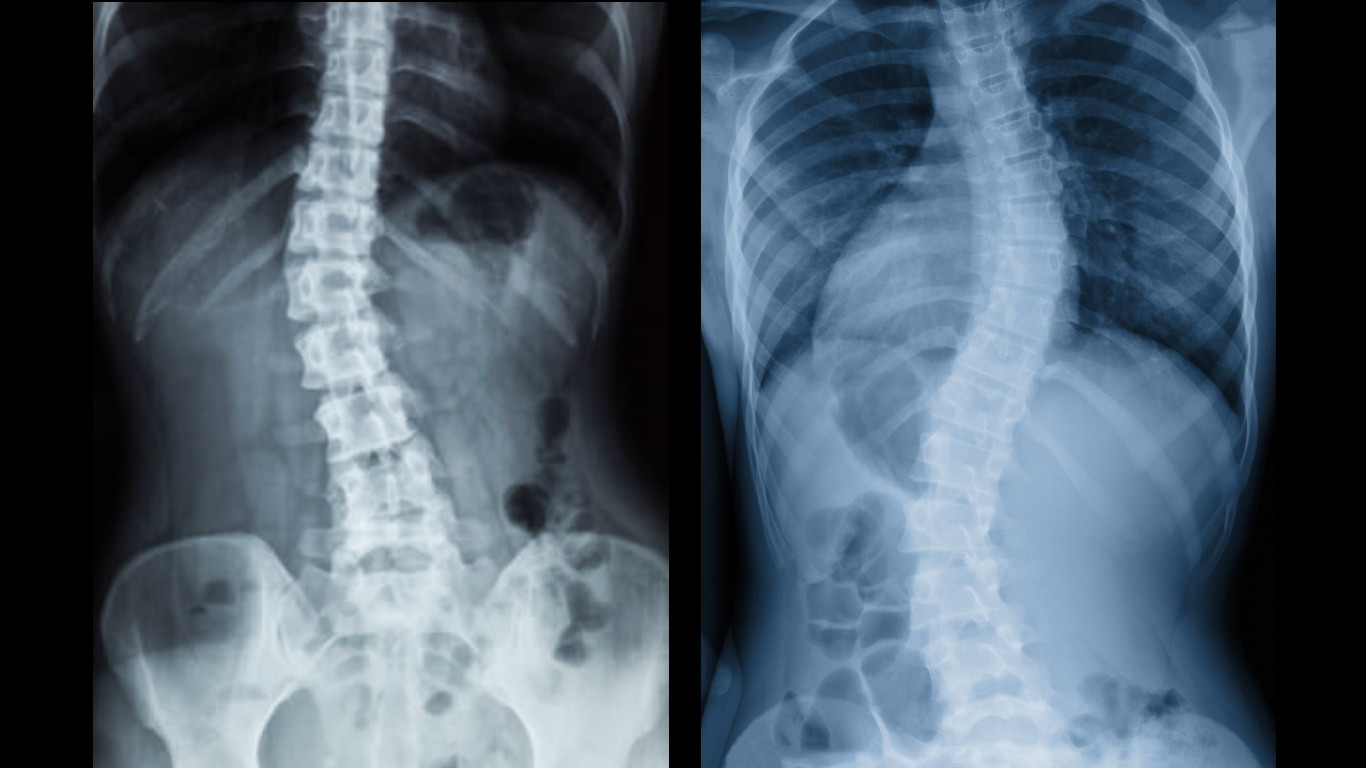

Scoliosis is a lateral curvature (side-bending) of the spine. A single curve in the spine is described as a C-curve. If the spine curves in both directions, it is described as an S-curve. If the degree of curvature is eleven degrees or more, it will be diagnosed as scoliosis.

Izquierda: curva C; Derecha: curva en S

Tipos de escoliosis

Approximately 85% of scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic,1 which means that the cause of the spinal curvature is unknown.

In cases of congenital scoliosis, the spinal curvature is a structural abnormality that is present at birth.

In cases of neuromuscular scoliosis, the spinal curvature is caused by a neurological or muscular disease, such as cerebral palsy, spinal cord trauma, muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, spina bifida, neurofibromatosis, or Marfan syndrome.

Efectos secundarios de la escoliosis

Roughly two-thirds of adults with scoliotic curves between 20 and 55 degrees experience back pain.2 Many people with scoliosis develop pain in other parts of their bodies due to their postural misalignment, which puts uneven stress on the hips, knees, neck, and shoulders. Arthritis, disc and nerve compression in the spine, and difficulty breathing are also common.

Many people with untreated scoliosis, as well as some who have been surgically treated, develop spondylosis.2 Spondylosis is an arthritic condition of the spine in which joints become inflamed, cartilage thins, and bone spurs develop. Disc degeneration or spinal curvature can lead to spinal vertebrae pressing on nerves, resulting in severe pain and requiring surgery.

Aparatos ortopédicos y cirugía: ¿son eficaces?

Typically, bracing is recommended for curves greater than 25 degrees. Bracing attempts to slow or halt curve progression by forcibly aligning the spine. However, studies show mixed results when it comes to the efficacy of bracing,3 and some experts believe that the practice of bracing is outdated and ineffective. Patients who wear braces can also experience negative side effects such as pain, restricted breathing, and weakening or stiffening of their muscles due to lack of movement.

When curves progress to 45-50 degrees or more, spinal fusion surgery is considered. About 38,000 people undergo spinal fusion surgery each year in the United States.4 In spinal fusion surgery, metal rods, hooks, wires, and screws are attached to the spine in order to force it into a straight position. Then doctors attach pieces of bone, which grow together and create the actual fusion of the spine. Patients who undergo this type of surgery lose 20 to 60 percent of their spinal flexibility.5 A great deal of strain is put on the unfused parts of the spine, leading to a high rate of disc degeneration and osteoarthritis. Research shows that 75% of patients experience degeneration in their sacroiliac joints after spinal fusion surgery.6 And sadly, more than 40% of spinal fusion patients experience no reduction in their pain levels.5

Las tasas de complicaciones en las cirugías de fusión espinal varían, pero son bastante altas en todos los ámbitos. Algunas investigaciones han demostrado que más de la mitad de las cirugías no tienen éxito, lo que significa que las vértebras en realidad no se fusionan. A pesar de que las vértebras se mantienen en su lugar mediante un hardware, los patrones de contracción en los músculos de la espalda provocan micromovimientos en la columna, lo que impide el crecimiento continuo del hueso. La contracción muscular puede ser tan fuerte que las varillas de metal insertadas a lo largo de la columna vertebral se rompen, causando mucho dolor y requiriendo una nueva cirugía. Dado el alto riesgo de complicaciones y la falta de evidencia que respalde la fusión espinal como un tratamiento efectivo, muchos médicos e investigadores ahora están de acuerdo en que la cirugía puede usarse para ralentizar o detener la progresión de la curvatura, pero poco más.

Las tasas de escoliosis idiopática aumentan drásticamente con la edad

A 2014 review published in American Family Physician found that approximately 85% of scoliosis cases are classified as idiopathic, or of unknown cause.1 So, 85% of the people who get diagnosed with scoliosis get no explanation as to what has caused it.

The same review found that between 2% and 4% of teenagers have scoliosis. According to a retrospective study done at Johns Hopkins University, the rate of scoliosis increases to more than 8% in adults over the age of 40.7 And a 2005 study of 75 healthy adults over the age of 60, with no previous diagnosis of scoliosis or spinal surgery, found the rate of scoliosis to be 68%.8

Esta creciente prevalencia con la edad es un fuerte indicador de que la contracción muscular por actividades repetitivas, lesiones y estrés, cuyos efectos aumentan con la edad, juegan un papel en el desarrollo de la afección.

Los complejos patrones musculares implicados en la escoliosis idiopática

Nuestra columna puede flexionarse (doblarse) en todas las direcciones: hacia adelante, hacia atrás y hacia cada lado. Cuando nos doblamos en cualquier dirección, también podemos rotar nuestra columna hacia cualquier lado. Dado que tenemos 24 vértebras articuladas (en movimiento) en nuestra columna cervical, torácica y lumbar, y muchos músculos diferentes que controlan el movimiento de nuestras vértebras, podemos desarrollar patrones únicos y variados de flexión y rotación de la columna.

Scoliosis is never as simple as a single sideways bend or curve in the spine. We always compensate or balance ourselves out by developing other muscular patterns, like rotating to one side, arching our back, or rounding forward.

Hablemos de algunos de los músculos más importantes involucrados en la escoliosis:

The biggest, strongest muscles in our core that flex our spine laterally are our internal and external obliques. Our obliques also rotate our spine, so any chronic tension in our obliques will likely create both a lateral curve and some degree of rotation.

The erector spinae group of muscles travels from the base of the skull and cervical vertebrae all the way down to the pelvis, attaching to each vertebrae and rib. This group of muscles both laterally flexes the spine and extends it, meaning that it arches the back. So, chronic tension in these muscles can create both scoliosis and hyperlordosis, or an exaggerated arching of the lower back.

The intertransversarii are small, short muscles that connect each individual vertebrae to the vertebrae above and below it in the cervical and lumbar portions of the spine. These little muscles laterally flex the cervical and lumbar spine. Since they are the deepest muscles in the neck and lower back, they are nearly impossible to touch or sense internally.

We think of the quadratus lumborum (QL) as a lower back muscle, but technically, it’s our deepest abdominal muscle. The QL attaches our lowest rib to the top of our pelvis, and connects to our first through fourth lumbar vertebrae. This strong muscle laterally flexes our spine to either side, laterally tilts our pelvis (hikes our hips up one at a time), and helps to extend our spine. So, chronic tension in the QL not only contributes to lumbar scoliosis, but also to functional leg length discrepancy and hyperlordosis.

The latissimus dorsi is the broadest muscle of the back, spanning from the lumbar and lower half of the thoracic spine all the way to the upper arm just below the shoulder joint. The latissumus dorsi participates in many actions: extending, adducting, and medially rotating the shoulder, laterally flexing the spine, extending the spine, and even tilting the pelvis forward or to the side.

The transversospinalis group of muscles are small muscles in between each vertebrae, similar to the intertransversarii. But this group of muscles rotates and extends the spine, contributing to both scoliosis and hyperlordosis.

The most important thing to take away from this discussion is the fact that the muscular patterns involved in scoliosis can be very complex. All of the muscles in the core of the body, including some we haven’t mentioned, will be involved in the lateral flexion, rotation, and extension or forward flexion of the spine, as well as in the compensatory patterns we develop in order to balance ourselves out.

El resultado de la participación de tantos músculos multifuncionales es que la escoliosis idiopática típicamente implica flexión lateral hacia uno o ambos lados, rotación hacia uno o ambos lados y extensión y flexión hacia adelante o ambas. Estos giros y torceduras pueden ocurrir en varias partes de la columna, creando patrones de curvatura espinal tan únicos como nosotros.

En la siguiente sección, hablaremos sobre cómo y por qué desarrollamos estos patrones complejos de contracción muscular.

And watch this video to learn how chronic muscle contraction pulls the spine into a curve.

Por qué desarrollamos la contracción muscular involuntaria que causa la escoliosis idiopática

Como mencioné al comienzo de la publicación, nuestros huesos no se mueven a menos que nuestros músculos los hagan moverse. Y nuestros músculos están controlados por nuestro sistema nervioso. Entonces, si alguno de los huesos de nuestro cuerpo se está desalineando, es porque nuestro sistema nervioso está enviando el mensaje a nuestros músculos para que muevan nuestros huesos de esa manera.

¿Por qué nuestro sistema nervioso enviaría el mensaje de hacer algo que podría dañar nuestro cuerpo? ¿Y por qué algunas personas desarrollan escoliosis y otras no?

The movement and level of contraction of our muscles is controlled by our nervous system. The way that our muscles move, and how much we keep them contracted, is actually learned over time by our nervous system.

Our nervous system learns certain ways of using our muscles based on how we choose to stand and move each and every day. Our nervous system notices the postures and movements that we tend to repeat, and it gradually makes these postures and movements automatic so that we don’t have to consciously think about them.

This learning process—that of developing what we refer to as muscle memory—allows us to go through the activities in our daily lives easily and efficiently. Unfortunately, if we tend to repeat unnatural postures or movements, our nervous system will learn those too. Our automatic neuromuscular learning process doesn’t discern what is good or bad for us—it just notices what we tend to repeat, and makes it automatic.

Por lo tanto, si lleva su bolso del mismo lado todos los días, sostenga a su hijo en la misma cadera, siéntese en su escritorio de la misma manera o adapte su postura a una lesión; los músculos que flexionan la columna hacia un lado pueden volverse crónicamente apretado, que conduce a la escoliosis idiopática.

As your nervous system gradually learns to keep your muscles tight, gamma loop activity adapts. This feedback loop in your nervous system regulates the level of tension in your muscles. As your brain keeps sending the message to contract your muscles, gamma loop activity adapts and starts keeping your muscles tight all the time. Meanwhile, your proprioception (your internal sense of your posture and movement) adapts so that you’re not aware of the increased level of tension in your muscles or your altered posture.

Muchas personas desarrollan contracciones musculares involuntarias que desalinean la columna vertebral de alguna manera; Tanto la cifosis postural (espalda redondeada) como la hiperlordosis (espalda baja arqueada) son muy comunes. La flexión lateral también es muy común, pero la curvatura lateral de muchas personas permanece a menos de 11 grados a lo largo de su vida, por lo que no se les diagnostica escoliosis.

“Después de sufrir varias lesiones en mi cuerpo, incluida una lesión en la espalda, mi columna en forma de S se volvió más severa y dolorosa. Probé varios ejercicios, fisioterapia y un curso de postura en línea para la escoliosis. Aparte de someterse a una cirugía de espalda, recomendada por un médico ortopédico, nada funcionó.

I hit the jackpot with the Somatic Movement Center. After the first month of doing exercises in the Scoliosis Course, my back and sciatica pain are basically gone. The sciatica pain only flares up occasionally if I lift a heavy object or sit on a hard surface. If the pain persists, I immediately do one of the somatic exercises with fairly quick results. After three years of chiropractic treatment, I no longer need to continue my visits. Thank you, thank you, thank you, Sarah, for this gift that keeps on giving!”

-Roz

Alivio de la escoliosis idiopática con pandiculación

Entonces, ¿puede liberar la contracción muscular involuntaria, restaurar la actividad normal del bucle gamma y volver a entrenar su propiocepción? ¡Sí tu puedes! La técnica de movimiento de la pandiculación le permite hacer todas estas cosas enviando información precisa a su sistema nervioso sobre el nivel de tensión en sus músculos.

Pandiculation releases subconsciously held muscular contraction and brings muscles back into voluntary control. Thomas Hanna incorporated the technique of pandiculation into his system of neuromuscular education called Clinical Somatic Education. Since this is already a long post, I’ll let you read more about pandiculation in this post.

La escoliosis causada por músculos tensos que desalinean la columna vertebral es un problema funcional; es causado por la forma en que funciona el sistema nervioso. Intentar mejorar una curva espinal funcional mediante el uso de fuerza manual, como un aparato ortopédico o hardware, no tiene sentido y, a menudo, es ineficaz, ya que no cambia los mensajes que su sistema nervioso envía a sus músculos para que se mantengan tensos.

Likewise, manual therapy like chiropractic and massage does not change the messages that your brain is sending to your muscles. Changing these messages requires retraining your nervous system using active, conscious movement: namely, pandiculation.

Los pacientes con escoliosis idiopática que utilizan ejercicios de somática clínica para liberar la contracción muscular crónica que está causando su curvatura típicamente experimentan una reducción o eliminación del dolor, así como un enderezamiento gradual de la columna. Los ejercicios de somática clínica son muy lentos, suaves y terapéuticos, y son apropiados para todas las edades y niveles de condición física.

For most people, idiopathic scoliosis does not have to be a life sentence. The earlier the condition can be addressed with neuromuscular education, the better. Years of pain and psychological suffering can be prevented with early, constructive intervention.

If you have idiopathic scoliosis and want to learn Clinical Somatics exercises at home, the best way to start is with Clinical Somatics for Scoliosis. This three-month online course teaches the exercises one-by-one through video demonstrationss, audio classes, and written explanations, and is an ideal way for beginners to learn the exercises at home.

“After doing the whole program of Sarah Warren’s – Clinical Somatics for Scoliosis and having read her book to understand exactly how somatics works, I managed to almost heal all my symptoms! My scoliosis unwinded and I can clearly see myself more elongated and almost straight in the mirror. Thank you Sarah. I am very glad I stumbled upon your website. Life saver.”

-Rawya Rotily

A continuación, se ofrecen algunos consejos generales que debe seguir a medida que avanza en el curso:

Become very familiar with your pattern of curvature so that you know how to go about releasing the muscles that are causing it. Here is a simple example: If your curvature looks like this from behind (see image below), it means that the muscles on the right side of your torso are tight, creating the curve that is concave to the right.

Trate de hacer que su columna se curve como la de la imagen, y sentirá que los músculos del lado derecho de su cintura se contraen.

As you learn the exercises, you should spend more time working with the muscles that are tighter. You can do more repetitions with your tighter side, and sometimes, you should try lying down and practicing the exercises only with your tighter side. When you stand up, you’ll feel unbalanced, but that’s part of the learning and adjustment process that your nervous system needs to go through. Be sure to do the Standing Awareness exercise before and after—this is a critical part of the process of adjusting your proprioception (your internal sense of your posture).

A medida que comience a relajar los músculos tensos y ajuste su postura, se dará cuenta de los diferentes patrones de tensión que tiene en cada lado de su cuerpo y descubrirá cómo trabajar con cada lado para liberar esa tensión.

When you do practice the exercises on both sides, notice how each side of your body feels different. Are you using your muscles differently on each side? Can you sense your muscles more on one side than the other? Do you feel like you have more control on one side than the other? Is one side tighter or looser than the other?

You can then go back and forth from side to side, learning from your more coordinated side. If a movement feels easy or “right” on one side, try to replicate that feeling and way of moving on your other side.

Above all, be patient with yourself. Releasing the complex patterns of muscular tension that cause idiopathic scoliosis is like peeling an onion. You’ll discover many layers—many patterns of tension—along the way. It takes time for the nervous system and the tissues of the body to adjust to new ways of standing and moving, so don’t try to rush the process. The most important thing is that you’re heading in the right direction.

¿Listo para empezar a aprender?

If you have idiopathic scoliosis and you want to learn Clinical Somatics exercises, the best place to start is Clinical Somatics for Scoliosis. This online course teaches the exercises through video demonstrations, audio classes, and written explanations, and is an ideal way for beginners to learn the exercises at home.

“I am 13 years old and recently diagnosed with right Thoracolumbar Idiopathic Scoliosis. My mum and I came across Somatic Movement Center sometime in August during the pandemic as we were looking for treatment options for my scoliosis. Based on how I was feeling and the fact that I was determined to get myself to a journey of healing, I began the course and for sure from the 1st day, I knew I was on the road to recovery. Never did I miss to do my daily course, I began feeling and experiencing a difference in my feeling. The course has made me feel amazing. Since the first time I tried it I felt a huge difference with my posture, pain and I felt soo relaxed that all my stress was gone. I have had such an amazing experience and I am grateful that I got to find Somatic Movement Center.

Thank you so much Sarah for this course. I feel more even and symmetrical and have been feeling even more relaxed, and whenever I feel pain I do the somatic exercises and it relieves all the pain I feel. I have even become more flexible and my muscles are not as tight as they were before. Thank you so much Sarah, you have no idea how much you have improved my quality of life and I am looking forward to continuing with Somatic Movement Center exercises to eventually aspire to have a normal spine again and more relaxed muscles.”

-Natasha Wanjiru

Referencias

1. Horne, J.P., R. Flannery, and S. Usman. (2014) “Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Diagnosis and Management.” American Family Physician 89, no. 3: 193–198.

2. Shah, S.A., MD. “Scoliosis.”

https://www.nemours.org/content/dam/nemours/wwwv2/filebox/service/medical/spinescoliosis/scoliosisguide.pdf

3. Davies, E., Norvell, D., and Hermsmeyer, J. (mayo 2011). “Efficacy of bracing versus observation in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis.” Evidence-Based Spine-Care Journal; 2(2): 25–34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3621850/

4. Information and Support. National Scoliosis Foundation. http://www.scoliosis.org/info.php

5. Weiss, H.R. and Goodall, D. (agosto 2008). “Rate of complications in scoliosis surgery – a systematic review of the Pub Med literature.” Scoliosis, 3, 9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2525632/

6. Ha, K.Y., Lee, J.S., and Kim, K.W. (mayo 2008). “Degeneration of sacroiliac joint after instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: a prospective cohort study over five-year follow-up.” Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 33(11):1192-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18469692

7. Kebaish, K.M., et al. (abril 2011) “Scoliosis in Adults Aged Forty Years and Older: Prevalence and Relationship to Age, Race, and Gender.” Spine (Phila PA 1976) 36, no. 9:731–736.

8. Schwab, F. et al. (2005). “Adult scoliosis: prevalence, SF-36, and nutritional parameters in an elderly volunteer population.” Spine (Phila PA 1976), mayo 1; 30(9):1082-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15864163

Lectura recomendada:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna