Comment le fascia affecte-t-il notre douleur et notre mobilité ?

Si vous souffrez de douleurs musculo-squelettiques ou de problèmes de mobilité, on vous a peut-être dit que votre fascia est tendu ou que vous avez des adhérences fasciales. Bien que cela puisse être vrai, les problèmes de fascias sont le plus souvent le résultat de la façon dont nous bougeons et utilisons notre corps. Dans cet article, vous apprendrez :

- Qu’est-ce que le fascia ?

- De quoi est fait le fascia ?

- Les différents types de fascias

- Pourquoi les problèmes surviennent-ils avec les fascias ?

- Pourquoi y a-t-il des nerfs dans les fascias et que font-ils ?

- Comment savoir si la douleur est causée par les fascias ou les muscles ?

- Autres moyens d'améliorer la santé des fascias et de réduire la douleur liée aux fascias

Qu’est-ce que le fascia ?

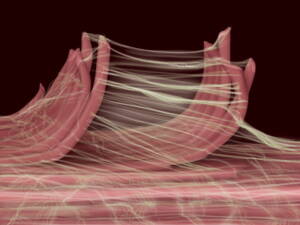

Le fascia est un type de tissu conjonctif. Il entoure, sépare et soutient tout dans notre corps, y compris nos organes, muscles, os, articulations, nerfs, tendons et ligaments.

Researchers don’t know everything about fascia yet, nor do they agree on a single definition. Several large groups of scholars have defined fascia in slightly different ways, and their definitions are discussed in this article. The broadest definition comes from the Fascia Nomenclature Committee:

« Le système fascial est constitué du continuum tridimensionnel de tissus conjonctifs fibreux mous, lâches et denses, contenant du collagène, qui imprègnent le corps. . Le système fascial interpénétre et entoure tous les organes, muscles, os et fibres nerveuses, conférant au corps une structure fonctionnelle et fournissant un environnement permettant à tous les systèmes du corps de fonctionner de manière intégrée.

De quoi est fait le fascia ?

Like other connective tissue, fascia is made mostly of collagen, the most abundant structural protein in the body. Fascia looks like a thin tissue, but it’s made of multiple layers of collagen. Between each layer is hyaluronan, better known as hyaluronic acid. Hyaluronan acts as a lubricant, allowing for smooth gliding between sublayers of fascia and between fascia and muscle.

Adhérences fasciales

Les différents types de fascias

Les fascias sont classés en différents types en fonction de leur fonction et de leur emplacement dans le corps :

Superficial fascia: This layer of fascia is located right under the skin, separating the skin from the muscle below it. Superficial fascia insulates, stores fat, and surrounds blood vessels and nerves.

Deep fascia: This type of fascia is more dense and fibrous than superficial fascia. Deep fascia surrounds the bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and blood vessels. It connects and provides essential support for these moving parts of the body.

Neural fascia: Often grouped into the category of deep fascia, this includes the meningeal layers and the connective tissues that envelop the peripheral nerves.

Parietal fascia: Sometimes grouped into the category of deep fascia, parietal fascia lines body cavities such as the pelvis.

Visceral fascia: This type of fascia surrounds the organs in our thoracic and abdominal cavities. It supports the organs, such as the lungs, heart, and liver, and keeps them in place.

Pourquoi les problèmes surviennent-ils avec les fascias ?

Fascia responds to movement, becoming looser with more movement and tighter with less. So, lack of movement—a sedentary lifestyle—is one of the most common reasons that fascia becomes tight. Fascia also becomes thicker, drier, and stickier as it tightens, limiting movement and making movement less comfortable.

In a similar way, limited range of motion and poor posture can lead to fascia tightening. Even if you are very active, if your chronically tight muscles are pulling you into an unnatural posture or limiting your range of motion, fascia in certain areas of your body—the areas in which your muscles are tight and movement is limited—can become tight.

Repetitive movements that overwork certain areas of the body can cause fascia in those areas to become tight. This is partly because muscles in those areas become tight from the repetitive movements, limiting range of motion. In addition, repetitive strain on certain body parts may lead to fascial adhesions developing (see below).

Surgery or injury can cause immediate structural damage to fascia. If healthy movement is resumed after the trauma, fascia can heal successfully, and no lasting effect may be felt. But the more that movement is limited after the trauma, the more likely it is that fascia will heal in such a way that range of motion may be limited or pain may be felt.

Adhérences fasciales are strands and sheets of fascia that stick to each other and/or to muscles, limiting movement and causing pain. They can occur as a result of any of the factors listed above: lack of movement, limited range of motion, repetitive movements, and trauma. In people who maintain a healthy level of activity, fascial adhesions are broken up and resorbed through movement. But a sedentary lifestyle allows adhesions to accumulate and worsen until range of motion and overall mobility is significantly restricted.

Adhesions limit the ability of the muscles to fully release and lengthen. Over time, they can cause muscles to become tighter and misalignment to develop simply because the muscles aren’t able to move through their full range of motion. However, it should be noted that most often fascial adhesions develop as a result of muscle tension and habitual body use, and not the other way around.

Pourquoi y a-t-il des nerfs dans les fascias et que font-ils ?

There are many sensory nerve endings located in fascia. Some of these nerve endings, called proprioceptors, detect changes in body position and acceleration of parts of the body. This sensory information is then sent to the brain, helping to form our internal sense of our body position and movement: our proprioception. Since fascia is located throughout our body, surrounding every muscle, tendon, ligament, bone, and joint, it is a rich source of sensory information and plays an integral role in our sense of proprioception.

Nerve endings that send pain information to the brain, called nociceptors, are also present in fascia. It has been observed that there are more nociceptors in pathological fascia than in healthy fascia. In other words, as fascia becomes tighter, drier, and thicker, more nociceptors form, sending more pain information to the brain and increasing pain sensation. This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint; our nervous system wants to make us aware that our fascia is becoming unhealthy due to lack of movement or trauma, so it increases the pain signals being sent to the brain.

Fascia is also densely innervated with a type of sensory nerve ending called mechanoreceptors, which detect touch, pressure, stretch, and vibration. Thermoreceptors, which detect changes in temperature, and chemoreceptors, which detect and respond to chemical stimuli, have also been found within fascial tissue. Other types of sensory nerve endings may be present in fascia as well. All of these sensory receptors contribute to our sense of the inner state of our body: our interoception.

Comment savoir si la douleur est causée par les fascias ou les muscles ?

Un fascia sain est doux et lâche et s’étire lorsque nous bougeons. Il permet à nos muscles et à nos articulations de bouger librement et sans douleur. Les fascias peuvent également absorber, stocker et libérer de l’énergie cinétique, ce qui nous aide à nous déplacer de manière efficace et puissante. Étant donné que les fascias font partie intégrante de notre capacité à bouger, les problèmes liés aux fascias peuvent souvent provoquer des douleurs musculo-squelettiques.

But, chronically tight muscles result in the same symptoms as tight fascia: stiffness, limited range of motion, and pain. Why? Because the activity of our muscles and the fascia that surrounds them cannot be separated; they move together. Where our muscles are tight and our range of motion is limited, it’s likely that our fascia is tight as well, and vice versa.

Dans nos pratiques quotidiennes de mouvement et de soins personnels, nous n’avons pas besoin de tenter de séparer l’activité ou les sensations de nos muscles et de nos fascias : nous pouvons les traiter comme un tout. Ils se desserrent tous deux en réponse au mouvement et à la chaleur, et se resserrent tous deux en réponse au manque d'utilisation, à la surutilisation et au froid. Ils peuvent tous deux potentiellement bien guérir après une intervention chirurgicale ou une blessure, ou développer des tissus cicatriciels ou des adhérences qui limitent l’amplitude des mouvements.

Alors, comment savoir si la douleur est causée par les muscles ou les fascias ? Dans de nombreux cas, c'est probablement les deux.

One factor that causes increased pain in tight or injured muscle and fascia is pathological sprouting of nociceptors (the pain receptors described in previous section). This means that more nociceptors grow in response to the tissue being unhealthy. The more nociceptors we have, the more pain we feel.

Another factor that may be present in some cases of muscle and fascia pain is inflammation. Pro-inflammatory substances have been observed in both unhealthy muscle and Fascia. These inflammatory substances activate nociceptors, causing pain.

Muscles that are chronically contracted are constantly using energy, and this process creates metabolic by-products. At least two of these, hydrogen ions and phosphates, can activate nociceptors and cause pain. When a muscle contracts and releases through its full range of motion and is not overused, these by-products don’t build up, and we don’t feel pain. It’s when muscles are fatigued during an intense workout or held in a state of chronic contraction that hydrogen ions and phosphates get a chance to build up, causing pain.

Sensitization of the nervous system also plays a role in both muscle and fascia pain. Sensitization describes changes that occur in both the central and peripheral nervous system when we feel pain for an extended period of time. Pain receptors become more sensitive, the spinal cord becomes more responsive to pain signals, and more neurons in the brain are recruited to respond to pain signals. Sensitization may affect muscles more than fascia, but researchers still have much to learn about fascia.

Autres moyens d'améliorer la santé des fascias et de réduire la douleur liée aux fascias

Nous avons établi que le mouvement est le meilleur moyen de garder vos fascias lâches et sains : restez actif, gardez vos muscles détendus, maintenez une posture et un alignement appropriés et évitez les activités répétitives. Mais si votre mobilité est limitée ou si une douleur chronique rend difficile le maintien d’une activité physique, que pouvez-vous faire d’autre pour améliorer la santé de vos fascias ?

Fascia becomes looser in response to heat, just as muscles do. Research shows that a temperature increase in fascia of up to 104°F (40°C) causes fascia to become less stiff and to stretch more easily. And as expected, cooling fascia causes it to become more stiff.

Nous pouvons produire nous-mêmes la chaleur nécessaire pour desserrer les fascias, simplement en bougeant. Lorsque nos muscles bougent, ils génèrent de la chaleur, ce qui détend les fascias qui les entourent. À mesure que les muscles et les fascias se réchauffent, les muscles deviennent moins limités par la raideur des fascias et l’amplitude des mouvements augmente.

When muscles are underused due to a sedentary lifestyle, muscle tissue gradually gets replaced by connective tissue. This limits movement and makes it harder to thoroughly warm up the connective tissue with movement. This can be the beginning of a vicious cycle in which fascia and other connective tissue becomes tight due to lack of movement, the tightness of the fascia then limits movement even further, and so on. Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) is one example of this cycle.

In situations such as this where a movement limitation or chronic pain prevents a person from warming up their own muscles and fascia through movement, external heat application can be very helpful. A heating pad, hot bath, or sauna are passive, accessible ways to heat up a specific area of the body or the entire body. Infrared light, which can be used in infrared saunas, panels, mats, body wraps, or hand-held devices, is proving to be an ideal source of heat. Infrared light penetrates into the muscle tissue and connective tissues, expanding blood vessels, increasing circulation, warming muscles and fascia, reducing pain and stiffness, and promoting healing processes.

Massage can also loosen fascia, albeit temporarily, just as massage temporarily loosens muscle tissue. This includes traditional styles of massage and myofascial release, both of which are performed by a trained therapist, and types of massage that you do to yourself (using a foam roller, rolling on a tennis ball, or using a hand-held massage tool).

Mechanoreceptors in fascia are responsive to manual pressure; so, pressure on fascia can lead to a temporary reduction in tension and increase in flexibility of the fascia.

Mais toute pression exercée sur le fascia s’exerce également inévitablement sur les fibres musculaires qui l’entourent. Ainsi, toute technique de massage dirigée vers le fascia masse également et relâche temporairement le tissu musculaire situé en dessous.

If the massage is done fairly gently, then the muscles may feel relaxed and loose for a while afterward. This is due to a temporary reduction in gamma loop activity. Within 24 hours or less, the muscles will tighten back up as gamma loop activity returns to normal. If the massage is done quite deeply, stretching the muscles much farther than they can voluntarily lengthen, then the stretch reflex will be triggered quickly. You may feel muscle soreness, pain, or an increase in tension soon after a deep massage.

It is possible that you may be able to improve the flexibility and health of your fascia by practicing movement exercises (especially pandiculation!) right after gently massaging and/or externally warming a tight area, while the fascia and muscles in the area are still loose.* This could interrupt the cycle of fascia tightening and movement becoming more limited, as described above.

*Veuillez noter que la plupart des gens n'ont pas besoin d'adopter cette approche lorsqu'ils pratiquent Somatiques Cliniques des exercices. Je suggérerais seulement d'utiliser de la chaleur ou un massage doux avant de pratiquer Somatiques Cliniques si vous avez affaire à une zone très étroite de votre corps qui semble insensible à la pandiculation. Si vous utilisez de la chaleur ou un massage doux pour détendre une zone de votre corps avant de pratiquer Somatiques Cliniques, assurez-vous de pratiquer vos pandiculations avec une extrême douceur, car les muscles peuvent être plus facilement tendus lorsqu'ils sont dans un état temporaire de relâchement anormale.

En conclusion : comment la fonction affecte la structure

So, we’ve learned how the function of our muscles affects the structure of our fascia. When our muscles are contracting and releasing through their full range of motion, our posture and movement are in alignment, and we stay active with a variety of different activities, our fascia stays loose and healthy. But when we become sedentary, develop misaligned posture or movement patterns, or engage in repetitive activities, our fascia becomes tight and unhealthy.

We cannot consciously, voluntarily control the way our fascia moves, but we can control the way our muscles move. And when our muscles have become chronically tight or our posture and movement have become misaligned, we can use Pandiculation to release our tight muscles and retrain our posture and movement patterns. As we do so, our fascia will adapt by becoming loose and healthy again.

Même si la santé de nos fascias fait partie intégrante de notre capacité à bouger librement et sans douleur, ne vous laissez pas entraîner dans la façon structurelle de regarder votre corps, aussi pratique que cela puisse paraître. Un fascia tendu et malsain n’est généralement qu’un symptôme d’une mauvaise utilisation du corps et d’une tension musculaire chronique.

Attempting to treat tight fascia with various types of massage or massage tools will only yield temporary results. You must pandiculate your muscles and retrain your posture and movement patterns in order to address the underlying cause of your tight fascia and to maintain healthy fascia as you age.

Lecture recommandée:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna