Síndrome de la Salida Torácica:

Anatomía, Causas y Tratamiento con Somática Clínica

El síndrome de la salida torácica puede parecer un poco aterrador, pero la mayoría de los casos son funcionales, lo que significa que se pueden prevenir y, a menudo, eliminar por completo.

Cuando los músculos tensos o una mala postura comprimen la salida torácica, puede experimentar síntomas como dolor y entumecimiento en el hombro, brazo y mano. En esta publicación hablaremos sobre la anatomía del síndrome de salida torácica, las causas más comunes de la afección y cómo los ejercicios de somática clínica pueden prevenirla y aliviarla.

¿Qué es el síndrome de la salida torácica?

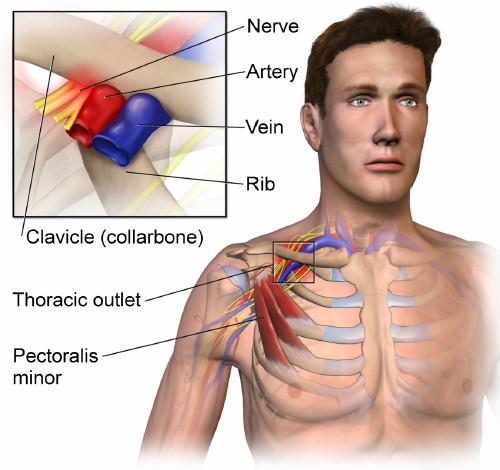

The thoracic outlet is a small space between the clavicle (collarbone) and the first rib (see image below). A bundle of nerves and blood vessels passes through the thoracic outlet and provides sensation, motor control, and circulation of blood to the chest, shoulder, arm, and hand.

The network of nerves that passes through the thoracic outlet is called the brachial plexus. The lower four cervical nerves and the first thoracic nerve emerge from the spinal cord, pass in between the scalene muscles in the neck, through the thoracic outlet, under the pectoralis minor, into the armpit, and down the arm. If the brachial plexus is compressed at any point along its path, you may feel the symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome.

Estos síntomas incluyen:

- Dolor en el cuello, el hombro o el brazo

- Entumecimiento u hormigueo en el brazo o la mano

- Debilidad o fatiga en el brazo o la mano.

- Falta de color en el brazo o la mano.

- Dedos, manos o brazos fríos

- Pulso débil o nulo en el brazo afectado

- Hinchazón en el brazo

¿Qué causa el síndrome de salida torácica?

El síndrome de la salida torácica puede ser causado por un problema estructural, como una costilla adicional, el crecimiento de un tumor o una lesión en el área. Pero más a menudo, el síndrome de salida torácica es un problema funcional, causado por una mala postura o por tensión muscular crónica en el cuello, el hombro y el pecho.

The nerves that form the brachial plexus emerge from the spinal cord in the neck. If you have forward head posture, your neck muscles will be tight and your cervical vertebrae will be compressed. This compression can lead to the nerves being impinged as they exit the spinal cord, and cause symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome.

The brachial plexus then passes in between the anterior scalene muscle and the middle scalene muscle. The scalenes flex the head and neck forward, bend the head and neck to the side, rotate the head and neck to the side, and elevate the ribs when we inhale. If your scalenes are tight, or if you have forward head posture or chronic tension in your neck, your brachial plexus may be compressed as it passes in between the scalenes.

The pectoralis minor is the muscle most commonly implicated in thoracic outlet syndrome. However, before the brachial plexus reaches the pectoralis minor, it passes through the thoracic outlet. The clavicular fibers of the pectoralis major attach to the clavicle, as does the deltoid muscle. Chronic tightness in these two muscles creates a downward pull on the clavicle, compressing the brachial plexus.

The brachial plexus then passes under the pectoralis minor. If this muscle is tight—we’ll talk about why it and the previously mentioned muscles get tight in the next section—it will compress the brachial plexus, and cause symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome.

¿Por qué desarrollamos la rigidez muscular crónica que causa el síndrome de salida torácica?

The muscles of the neck, shoulders, and chest that we discussed in the last section become tight as a result of the way we use our body every day. If we engage in activities or adopt habitual postures that involve flexing the head and neck forward, rounding the shoulders and upper back, and rotating the shoulders inward and bringing our arms in toward our body, we can easily develop the patterns of muscular tightness that lead to thoracic outlet syndrome.

Algunas causas comunes del síndrome de salida torácica son:

- Trabajando en una computadora

- Pasar largos períodos de tiempo mirando hacia abajo en un dispositivo móvil

- Practicar deportes como béisbol, natación y gimnasia.

- Levantamiento de pesas

- Tocando un instrumento musical

- Sostener a un bebé durante largos períodos de tiempo

- Llevando una maleta pesada

El síndrome de salida torácica también ocurre cuando las personas han tenido una lesión como un brazo roto y deben mantener el brazo en cabestrillo durante un período prolongado. Los músculos del cuello, los hombros y el pecho se tensan debido tanto a la falta de uso como a la protección instintiva del área lesionada.

He aquí por qué nuestros músculos se tensan cuando los usamos en exceso:

The movement and level of contraction of our muscles is controlled by our nervous system. The way that our muscles move, and how much we keep them contracted, is actually learned over time by our nervous system.

Our nervous system learns certain ways of using our muscles based on how we choose to stand and move each and every day. Our nervous system notices the postures and movements that we tend to repeat, and it gradually makes these postures and movements automatic so that we don’t have to consciously think about them. Part of this process of automation is that our nervous system starts keeping certain muscles partially contracted all the time—this saves us time and conscious attention in carrying out repetitive actions. (Really, our nervous system is trying to be helpful!)

This learning process—that of developing what we refer to as muscle memory—allows us to go through the activities in our daily lives easily and efficiently. Unfortunately, if we tend to repeat unnatural, potentially damaging postures or movements—like certain types of athletic training, heavy lifting, or repetitive daily activities like working at a computer or carrying our baby on one side—our nervous system will learn those too. Our automatic neuromuscular learning process doesn’t discern what is good or bad for us—it just notices what we tend to repeat, and makes it automatic.

As our nervous system gradually learns to keep our muscles tight, gamma loop activity adapts. This feedback loop in our nervous system regulates the level of tension in our muscles. As our brain keeps sending the message to contract our muscles, gamma loop activity adapts and increases the resting level of tension in our muscles. Meanwhile, our proprioception (how we sense our body) adapts so that we’re not aware of the increased level of tension in our muscles.

Este proceso innato de aprendizaje muscular tiene lugar a lo largo de nuestras vidas. Por lo general, ocurre de manera tan gradual que no nos damos cuenta hasta que notamos los efectos: tensión o dolor, postura antinatural, movimiento limitado o daño estructural en nuestras articulaciones y tejidos conectivos.

Cómo aliviar el síndrome de salida torácica con ejercicios de Somática Clínica

Para prevenir y aliviar el síndrome de la salida torácica, necesita liberar la contracción crónica de los músculos del cuello, los hombros y el pecho, así como los abdominales. Los abdominales suelen estar tensos en las personas con síndrome de salida torácica debido a su tendencia a redondearse hacia adelante, llevando la caja torácica hacia abajo.

If you try stretching or getting a massage to release your tight muscles, you’ll likely find that these approaches provide only temporary lengthening of muscles. Your muscles will tighten back up within a few hours due to the stretch reflex. Static stretching and massage do not change the messages that your nervous system is sending to your muscles to stay tight—active movement is necessary to retrain the nervous system.

The most effective way to reduce the tension in your muscles is with a movement technique called pandiculation. The technique of pandiculation was developed by Thomas Hanna, and is based on how our nervous system naturally reduces muscular tension. Pandiculation is the reason why Hanna’s method of Clinical Somatic Education is so effective in releasing tension, retraining posture, and relieving pain. Hanna created many self-pandiculation exercises that can be practiced on your own at home.

Pandiculation sends accurate feedback to your nervous system about the level of tension in your muscles, allowing you to change your learned muscular patterns, release chronic muscle tension, and retrain your proprioception. You can read more about pandiculation in this post.

If you’ve learned Clinical Somatics exercises from my online courses or from another Certified Clinical Somatic Educator or Hanna Somatic Educator, you can use this section to help guide you in releasing the muscles that are causing your thoracic outlet syndrome. If you’re new to Clinical Somatics, the best place to start is the Level One Course.

Ahora, algunos ejercicios específicos. Estos son los ejercicios del Curso de Nivel Uno que ayudan a aliviar el síndrome de salida torácica:

Arch & Flatten: I recommend practicing this every day. It’s best to begin your practice with this exercise, because it gently releases the abdominal and lower back muscles and prepares you for the rest of your practice.

Arch & Curl: Practice this every day. Really squeeze your shoulders together as you curl up. Release your abdominal muscles as slowly as you possibly can on the way down, imagining that you’re resisting gravity. Then, release your shoulders down and elbows out to the side as slowly as you possibly can—try counting to 16 or more as you release.

Side Curl: This exercise releases the obliques; however, these can play a role in your TOS if your obliques are tighter on one side, pulling your rib cage down and causing you to round your shoulder forward. So, be sure to practice the Side Curl on the side in which you have TOS. To do this, lie down on your opposite side, and practice this exercise curling up to the side on which you have symptoms. Really try to get a sense of the muscles on the side of your waist contracting, then release them as slowly as you possibly can—resist gravity as you lower down. Completely relax for a few moments before repeating the movement.

One-Sided Arch & Curl: This exercise gives you the opportunity to do the Arch & Curl while focusing on just one side at a time. Like with the Side Curl, you can practice this just with the side in which you have TOS. To do this, lift up your knee on the side on which you have TOS, put your hand on the same side behind your head, and practice the exercise.

Diagonal Arch & Curl: This exercise is an important one for TOS sufferers to do on a daily basis, as it releases the pectoral muscles. Like with the two previous exercises, you can practice this just with the side in which you have TOS. To do this, bring your hand up behind your head on the side in which you have TOS, lift up your opposite knee, and practice the exercise.

Washcloth: You can practice this exercise as instructed, going back and forth from side to side. When rolling your shoulders forward and backward, notice how your right and left shoulders feel different. You can learn a great deal about your body by comparing your two sides. Feel free to practice just the upper body part of this exercise so that you can focus completely on the movement of your shoulders.

Flowering Arch & Curl: You can practice this exercise as instructed, and like the Washcloth, feel free to practice just the upper body part of the exercise so that you can focus completely on your shoulders and chest. The upper body part of this exercise is an important one for TOS sufferers to do, as it releases the pectoral muscles.

Y más ejercicios del Curso de Nivel Dos:

Head Lifts: This exercise releases the neck muscles and corrects forward head posture. If you have TOS, you should do this exercise on a regular basis. Practice this after you’ve warmed up your abdominals and lower back muscles with the Arch & Flatten and Arch & Curl.

Scapula Scoops: Both parts of the Scapula Scoops are important for TOS sufferers. Part 1 helps to release the scalene muscles, and Part 2 releases the pectoral muscles. You can practice these as instructed, or do them just with the side in which you have TOS.

Diagonal Curl: This is a very important exercise for TOS sufferers, as it releases both the abdominals and pectorals. To practice this just on the side in which you have TOS, lie down on your opposite side, put your hand behind your head and let your upper body rotate open, and practice the exercise.

Shoulder Directions: This exercise releases the shoulder and chest muscles, and develops fine control of shoulder movements in all directions. To practice this just on the side in which you have TOS, lie down on your opposite side and practice the exercise.

Finally, be aware of how you’re using your body as you go through your daily life. Your progress with the exercises will be slower if you continue to do activities or habitual postures that are keeping you stuck in your patterns of tension and exacerbating your symptoms. Notice the tension that you hold in your neck, shoulders, chest, and abdominals, as well as how you might be using the sides of your body differently when you:

- Carry your bag or your child: Do you always use the same side? Do you round one shoulder forward, rotate it inward, and bring it in toward your body?

- Work at a computer: Do you use a mouse with the same hand a great deal? Do you spend a lot of time typing with your shoulders rounded forward and rotated inward? Do you bring your head and neck forward?

- Exercise: Do you lift weights or play sports that require throwing with one arm or using the chest and shoulders a great deal?

- Relax on your couch: Do you slouch down, rounding your upper back and shoulders?

- Sleep: Do you sleep more on one side than the other? Sleeping on your back is best; put a pillow under your knees if that makes you more comfortable.

¿Listo para empezar a aprender?

If you’d like to learn Clinical Somatics exercises at home, the best place to start is the Level One Course. This online course teaches the exercises through video demonstrations, audio classes, and written explanations.

Lectura recomendada:

The Pain Relief Secret: How to Retrain Your Nervous System, Heal Your Body, and Overcome Chronic Pain by Sarah Warren, CSE

Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility and Health by Thomas Hanna